Elegiac Negotiations: Neville Dawes via Kwame Dawes’s Eyes, by Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto

“It’s evident,” writes Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto, “that the mix of Kwame Dawes’s bicontinental heritage and love for his father and household has bestowed an elegiac temperament upon his work.” The next essay meditates on the son’s elegiac negotiations going down in Dawes’s work.

I: Dying and Concern

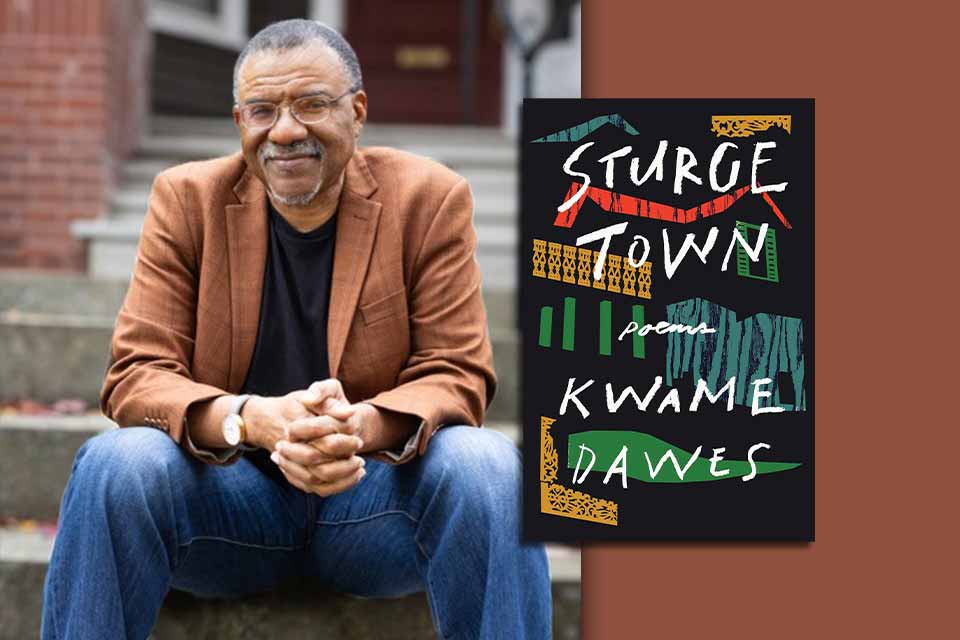

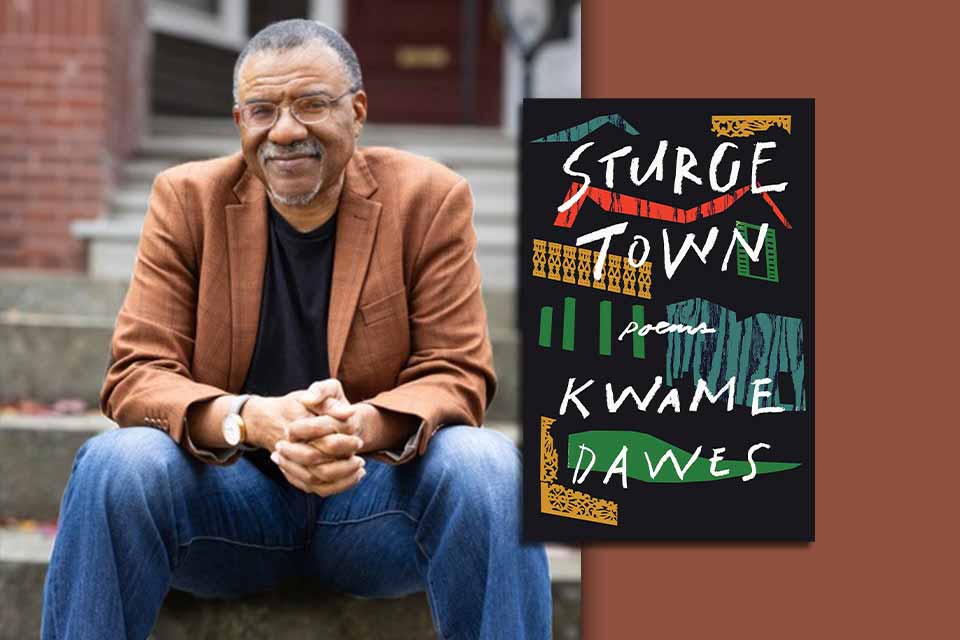

Kwame Dawes (b. 1962) has constructed an impeccable status as a poet, writer, playwright, professor of literature, and co-curator of the extremely influential African Poetry E-book Fund. This fund has printed virtually each recognizable African poet working immediately because it was launched over a decade in the past in 2012. Away from his curatorial status, Dawes is a consummate poet of contemplation and sage understanding of the scrim and scram of up to date Black life as it’s. In a profession that has spanned over thirty years, he has printed a number of works, together with poetry collections, novels, and memoirs.

Nevertheless, the crux of his poetry is its dwelling on elegiac negotiations of familial grief. Quite a few poems broadly discover questions of fatherhood. One particular poem in Narrative Journal, “The Forgettable Life,” about his father-in-law started thus: “I do marvel the way it’s inside him to reside unknown or unknowable.” The poem attracts parallels, wittingly or unwittingly, between his spouse’s father and his father. It chronicles the intertwined histories of Caribbean lives—the sameness, the similarity if you’ll—of the journeys and experiences of Caribbean households. But when these lives are unmemorable, why would Dawes label it “forgettable”? Maybe he solely searches for that forgettable high quality, that which is understood:

I do consider how

we reside out these full lives unseen

by those that ought to know, and the way at dying,

the lasting scent of issues fades with us

inside tidy compartments, the manageable, the compact

world we attempt to hold as a container of chaos

that even we don’t suppose to maintain.

Looking for to know the “unknown” and “the unknowable” appears to be the compass that guides Dawes’s explorations of his father’s life (and the unknown and the unknowable are clearly life and dying). Main components of his poetry not solely examine and interrogate his father’s life, however via Dawe’s use of language we regularly really feel that this fixation with fatherhood interprets on to self-examination—that’s, painstaking selecting at his personal life, which is partly by way of the lifetime of the marginally itinerant father.

Dawes’s father, Neville Dawes (1926–1984), was born in Warri, Nigeria, to Jamaican mother and father who have been Baptist missionaries. Neville spent his adolescence in Jamaica, the place his mother and father had returned when he was three years previous. He studied English at Oriel School, Oxford, and later taught English on the College of Ghana. Whereas there, he married a Ghanaian lady, Sophia, and in 1962. All through his lifetime, Neville constructed a robust status as a notable Caribbean author with an emphasis on novels and poetry. His son Kwame’s double African and Caribbean heritage closely influences his work. However the essential hyperlink is his father’s personal itinerary and connections to Africa, a spot the place fable and modernity—the unknowable and the knowable—appear to coexist; the identical countenance may be very current in Caribbean tradition. In his memoir, Removed from Plymouth Rock (2007), Dawes writes of a wierd incident that occurred upon his father’s dying, which he felt was a part of a considerably haunting feeling he skilled whereas dwelling in Kingston, Jamaica:

The hauntings have been surprisingly intense when my father died. Like the enormous moth that took up residence in my workplace the day after his dying. This moth wouldn’t go away, it doesn’t matter what I did. I used a brush and brushed it out of the room. I shut the door and felt happy that it was gone. The following morning, it will be within the nook once more. It had flown in via the louvers over the door. I couldn’t shut the louvers. I used to be tempted to kill the factor, however a pal warned me towards that. He stated that he was fairly clearly my father coming to go to me for some time earlier than his journey residence. I didn’t purchase this, however I discovered a wierd attraction within the notion. I discovered that the presence of the moth introduced me some peace of thoughts, and I used to be comforted by the parable. (53)

Dawes goes into larger element all through the guide, making an attempt to make sense of this fable. Since he doesn’t see himself as a superstitious individual, he considers it a pure results of his grief over his father. But he locations a level of significance on it as he contemplates the that means of dying, the sensation of dying and loss. The explanation for that is clearly his sentimental attachment to his father’s reminiscence and his twin African heritage, that of Ghana in Africa and Jamaica within the Caribbean archipelago. The view of dying in these two cultures sitting on reverse sides of the Atlantic privileges the unknown that exists outdoors the realm of human life; the act of mourning is ritualized in a tradition of meanings and layers of dread. Thus, dying and the way mourning occurs is culture-specific.

Dawes is totally conscious of this when he admits that “dying goes past the mere hurting of the guts. It’s grounded within the panorama” (55). Deaths in Ghana and Jamaica keenly drew him right into a stronger reference to each locations. From right here, Dawes’s elegiac investigation of his personal strategic response to his father’s dying begins to make sense to us. It lies fully in his determination to reside and pursue his profession in America moderately than full his residency in Ghana or Jamaica. America was a rustic his father exercised a deep mistrust for and prevented any interactions with throughout his lifetime, so the concept that we finally get from Dawes’s writing about his father is the son’s understated sense of his personal guilt and betrayal of his father’s lifelong stance.

II: The Depth of a Poet’s Elegies

A poet acts out his grief with poetry; a poet performs mourning likewise. Dawes’s poetry is closely punctuated by references to his father. What we observe is {that a} poet at all times finds a strategy to negotiate connections, and right here it’s the connection each as a father-son relationship and between the older author and the youthful one. Neville Dawes had written a poem, “Acceptance,” devoted to his spouse, Kwame Dawes’s mom. (“Acceptance” can be the roving, detailed tribute Dawes’s father-in-law may have written for his personal spouse. We get that image from “The Forgettable Life.”) Dawes had been particularly moved by that poem—and he considers it, it appears, the quintessence of spousal grief. The second part of his guide of poetry Resisting the Anomie (1995) is devoted as a response (typical of the “after . . .” poems subgenre) to that earlier poem by his father.

A poet acts out his grief with poetry; a poet performs mourning likewise.

“After ‘Acceptance,’” the primary poem within the second part of the aforementioned guide, picks up the place his father’s poem stopped, but it surely nicks a selected picture from the sooner poem, “wrinkled fingers,” utilized by his father to discuss with the love sustained in dying moments. In Dawes’s after-poem, he provides us a transferring autobiographical image of rising up within the shadow of his father: “Crafting your goals / from the tattered books / trainer Dawes crammed / onto his cabinets” (41). From right here, Dawes paints pictures of childhood bliss, highway journeys taken on the coastal roads of Jamaica, the paradisiacal idyll of the island. Evidently because the poem strikes additional and additional in, we come to understand the fantastic thing about a quintessentially middle-class Caribbean family and the cultural mores that cocoon it.

And the mores proceed to prevail as he writes across the departed presences of his mother and father: “Possibly your ghosts hover above the home at nights . . . / You come back morose, having finished your a part of touching the / dwelling earlier than daybreak” (45). Recall that Dawes denies he was superstitious in his memoir, however right here he appears to be taking part in a type of myth-making, an enshrinement, along with his mother and father’ ghosts. Apparently, he makes use of strategic prepositions and verbs equivalent to “hover,” “return,” “touching,” as if his longing is to make their presence concrete. Evidently Dawes is not only interrogating his reminiscences from their reminiscence and from supplies his father left; he additionally appears to be extending it. From his reminiscence of the idyllic panorama of his childhood, he writes within the poem: “I can see her bandannaed there / sharp calico towards the hill’s gray / her wrinkled fingers outstretched, trembling / her eyes glowing” (44). In one other part of the identical poem, he writes: “I reward this stuff / freed by her wrinkled fingers” (46). All emphasis right here is on the phrase “wrinkled fingers.” The wrinkled fingers of a girl close to dying or the wrinkled fingers of time’s atrophy on the human pores and skin. Whichever it’s, we all know {that a} wrinkle is a element of growing older and that its repetition is the poet’s negotiation of not simply his father’s poetic elegy to his deceased spouse but in addition his personal searching for to grasp dying and its actions on his household.

In his autobiographical assortment Not possible Flying (2006), Dawes once more views his father underneath the microscope. Within the poem “Pre-Mortem,” he dwells on the vibrancy of his father’s life earlier than dying whereas hovering across the picture of Sturge City, the place his father had grown up. From his view, this being one of many earliest mentions of this city in his poetry, it’s a place that’s typical of Jamaica—the music, the meals, the air. However it’s a place that had fashioned his father and lends itself to a greater understanding of what might be recognized about him. It’s this reminiscence of Sturge City that he revisits when searching for an understanding, which he appears to search out in levels via his father’s fraternal relations: “I do know / that on this I’ve discovered the thriller of his calm / acceptance once you died these months / later, in one other season, on one other acquainted night time” (34).

Dawes’s most up-to-date assortment, Sturge City (2024), coalesces all of the ancestral connections of the Dawes household in Jamaica right into a type of family tree of actions. The Dawes household originated in Sturge City in St. Ann’s Parish, Jamaica. The city was one of many earliest free villages within the nation within the aftermath of slavery and dates again to 1839. Dawes makes use of the historic reminiscences of the household residence in Sturge City as a metaphor within the narrative linking his origins again to Africa, Europe, and now America. He locations his story as his household, narrowing down on his life and his strivings, however above all, he makes fable out of the familial actuality, each literal (as in dying) and metaphorical (as in journeys).

This assortment primarily focuses on his household, so a few of the poems on this masterly work contact on his father. The primary poem we encounter right here on this topic is “Welsh,” addressed on to his father. Once more, this poem is sort of a reminiscence, doubtless a narrative informed by his father. Someday in 1949, Neville Dawes—a Black man, evidently—had been mistaken in a pub as a fellow Welshman by a gaggle of Welsh coal miners whose white pores and skin had turn out to be blackened by coal:

the regulars

have been so coal-stained they known as

themselves niggers, they

thought a person who may play

the piano such as you, drink such as you,

run 100 yards such as you,

and fill your pipe with aroma

such as you, needed to be a minimum of

pretty much as good because the worst Welshman (22)

It’s an fascinating little bit of wry humor and yet one more footnote of unveiling who Dawes Sr. was and why his son now grieves him via the a number of interfaces of poetry. However it seems that the true grief right here is for the rules of household values that the elder had taught the youthful.

One other story, within the poem “A 12 months,” goes again to 1962 when Dawes was born. It’s curious how the poet speculates on the reactions to his start. Although there are actual indications right here that that is nonetheless a part of the intergenerational legends which can be informed in most households—once you have been born in so and so, such and such occurred—however right here we’re seeing Dawes’s father in full view. How does a person react when a son is born to him? Because it occurs, this was a author fathering a would-be author. What’s fascinating right here is the mundane wrestle of survival:

so, 1962 was a 12 months of nice second:

my father had a second son, had a guide

doing the rounds of evaluations,

was as a lot a author as he would

ever be. It was his greatest second

regardless of the doldrums he felt trapped in,

regardless of his impatience for glory

(he wouldn’t know this for years). (38)

Dawes sees himself considerably as a prodigal who had deserted his father’s values searching for America.

However there are hints of guarantees and guilt over failed guarantees. That is what we glean from the eponymous poem, “Sturge City,” As the traditional household residence within the historical Sturge had gone to ruins, Dawes makes a metaphorical connection between that abandonment and his personal life. He sees himself considerably as a prodigal who had deserted his father’s values searching for America. And nonetheless, he feels that he’s remedying that abandonment within the current by retaining reminiscence alive in his personal method:

For too lengthy I spoke of return, a sort

of prodigal fantasy, though, face

set towards the solar, I had deserted

the waywardness of the failed son.

My father is lengthy useless, and I used to be

trustworthy to the final. Nonetheless, postcolonial

that I’m, I constructed my very own fable

of departure, put aside the romance

of the exile for the pragmatics

of household and mission. (32)

In Sturge City, Dawes’s give attention to fatherhood comes full circle: the main target shifts from his father to himself in some unspecified time in the future. It looks like the transition of the reins of relevance from one era to the opposite, and he acknowledges this at all times with a sure poignancy, even unhappiness. The poem “No Pleasure’s Prophet” takes that reflective pose, a contemplation of time. He muses on how far he has come from his father and the way his personal kids have moved on from him to turn out to be their very own fathers and fogeys: “I do know I’m not pleasure’s prophet, only a father / recounting moons handed, / nervous that each phrase / I say will annoy them, indolent to my warnings” (49). It’s a melancholy remark: “At this time my kids, / their lot as soon as mine — with lease, payments, infants, / new spouse — have stated farewell to youth” (49). For Dawes, his father has turn out to be a part of the household legend in addition to his personal image of fatherhood—his overriding curiosity is in self-reflection. That’s, it’s also about himself. Dawes’s elegies subsequently vary from dispatches of grief to full-blown philosophical questions on dying, life, time, motion, and alter.

III: Later Places

Taken collectively, an entire autobiography of his father may very well be customary out of Dawes’s works. It’s a fixation hooked up to sturdy household connections, however it’s also a fixation {that a} youthful author could have for an elder who has immensely influenced him. Dawes has unceasingly negotiated his life in his poetry; a great a part of that oeuvre additionally interrogates his father’s experiences. There are too many tales informed concerning the older man in these works, so we essentially discover most references touching again to the daddy or a minimum of the household.

Dawes has unceasingly negotiated his life in his poetry; a great a part of that oeuvre additionally interrogates his father’s experiences.

Dawes’s 2001 assortment, Midland, co-opts the Black expertise into his father’s expertise. Extra Black experiences, each as a father and being fathered, are discovered not in solely Midland but in addition in Removed from Plymouth Rock. These experiences supply prismatic views of what Dawes and Dawes’s father have been, or weren’t, bodily and mentally. The poem “Ska Reminiscence,” devoted to his father, excavates one other reminiscence—a vortex of pictures, streets, historical past, and music—however it’s yet one more occasion of a reminiscence during which the daddy teaches his son the that means of life, clichéd as which may be. A number of poems discover their energy within the mythmaking of a mixture of city life and household. Poems right here appear to come back from the identical place whence the memoir Removed from Plymouth Rock emerged: the American expertise, an affect that will turn out to be essential in Dawes’s poetry.

The concept of “Midland” implies a location someplace, and for the poet who’s after all now not resident in Jamaica and even Ghana, it his maternal nation, the place he by no means actually lived for lengthy. In direct phrases, the Midland is known as a metaphor for midlife. The poet is coming to a long-overdue understanding of his personal life as he approaches center age. He has come into his personal and can be attempting to grasp what it’s for him to be in America (in South Carolina at that time). An incredible many issues hassle him, amongst them racism: “I’ve returned to South Carolina . . . on whose southern banks New World / Kurtzes rave among the many natives” (45).

Within the assortment Nebraska, from 2019, Dawes chronicles one other side of the American expertise. Attaining standing and changing into a famous mentor of poetry himself comes with its personal reflections. With this in thoughts, he begins the primary poem thus: “Now that I’ve my thorn within the flesh / I can write epistles, holy writs” (3). The overriding picture right here is of winter, the literal winter in addition to the winter of life, during which the poet finds himself exercising extra restraint and changing into extra circumspect. However winter additionally evokes dreariness. And right here the poet comes once more to dwell on dying and grief; thus the silent “dying” climate of 1 place brings acquainted reminiscences. To level to at least one poem, “The Immigrant Contemplates Dying” appears too consumed by morbidity. However we see it’s as soon as once more Jamaica and Neville Dawes, and the Dawes’s lineages, which can be gone: “This / is what I can say of exile; / a physique like me has misplaced monitor / of the narrative of mortality,” he writes (7). And eventually this knowledge and realization:

I used to be born

in a metropolis that become

a village inside listening to

distance, and the deep crimson

the soil of Accra is aware of it’s

at all times ready for the deep

heat of cankering our bodies,

for the spirits that deal with

the bushes and roads as momentary

dwellings earlier than the teeming

beneath of efficiency. In Kingston,

I thought-about dying every day,

its friendship with the dwelling

and we die as if the physique

was made for this. (7)

It’s evident that the mix of the poet’s bicontinental heritage and love for his father and household has bestowed an elegiac temperament upon his work. His poems, certainly his writing, will at all times muse about dying, grieve in addition to philosophize it, for as people we lose and the earth positive aspects with the demise of every human flesh, the our bodies of individuals we love. It’s our destiny; as Dawes places it: “we die as if the physique was made for this” (8).

Dawes’s writing will at all times muse about dying, grieve in addition to philosophize it, for as people we lose and the earth positive aspects with the demise of every human flesh.

By the tip, this finish, we’ve an image of Neville Dawes via Kwame Dawes’s eyes, a outstanding trainer, author, administrator, music man, pal, household man, a person in love along with his spouse, in love with life, a sure Christian, a doable socialist, a wise man, and a mentor to his little children. Having all these qualities, it’s straightforward to see why Dawes dwells at all times on his reminiscence, why he painstakingly negotiates life via his reminiscences, and by so doing make sense of his personal peculiar grief. Or, we will say, writing all of it down in his poetry is his personal type of grieving.

Lincoln, Nebraska

0 Comment