Generally It IS Concerning the Analysis

At the moment’s publish is by creator, e book coach and historian Christina Larocco.

Almost a decade in the past, I labored as a marketing consultant on a mission to digitize manuscript collections associated to the ladies’s rights motion within the Philadelphia area, the place I reside. It was an amazing job: I spent the summer season of 2016 going from archive to archive, devouring the writing of activists each well-known, like Lucretia Mott and Alice Paul, and fewer so, like Martha Schofield.

Schofield was born in 1839 to a household of religious Quaker abolitionists whose household farm was a cease on the Underground Railroad. She attended girls’s rights conventions together with her mom as early as 1854, and in her thirties and past she devoted herself to the girl suffrage motion. Through the Civil Struggle, she volunteered at a neighborhood hospital, which took in a whole lot of United States troopers wounded at Gettysburg and elsewhere. From 1865 till her demise in 1916, she taught freed folks in South Carolina and tried to stem the tide of racial terrorism throughout the nation.

When the mission was over, I beneficial that Schofield’s letters and diaries be digitized. A part of this was egocentric: I had fallen in love with and began to jot down a e book about her, and I needed to have the ability to proceed my analysis at residence in my pajamas. However the cause I fell in love together with her was that her papers had been so totally different from something I had come throughout in my twenty years as a girls’s historian, then or since. It didn’t appear to be an moral dilemma.

Guides to girls’s paper collections usually challenge a model of this disclaimer: “scant details about her private life.” The primary era of girls’s historians was understandably centered on highlighting extraordinary girls’s accomplishments, disentangling them from residence, household, and the private or non-public to indicate what that they had executed within the public realms of politics, science, and the humanities. For generations, it was solely girls whose lives adhered to male fashions of feat whose papers had been deemed worthy of amassing. On the identical time, many public girls—or their descendants, who had been involved with propriety—purged their information of something private.

Schofield, nevertheless, wrote about her ideas and emotions continuously. It was this entry to her inside life, not her spectacular resume, that made me wish to write about her.

Now, a part of me worries that digitizing her papers has diluted their energy, exactly within the space that first attracted me to them.

Right here’s an instance: one of many challenges I confronted in writing about Schofield was determining tips on how to characterize her relationship with Robert Okay. Scott, a Civil Struggle normal, assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the Reconstruction governor of South Carolina. He and Martha first met in 1866, as he traveled by the state. Late in life, Schofield confessed in each a poem and a letter to her niece that she had cherished him. However you wouldn’t comprehend it based mostly on her extant writing from the time—she not often referred to him by title, and he or she by no means recognized him as greater than a good friend.

She did depart behind clues to those deeper emotions, although—sarcastically, extra in her makes an attempt to cover them than anyplace else. As forthcoming as Schofield was, she had a behavior of destroying supplies she didn’t need folks to see. In 1862, she destroyed a bunch of letters from faculty associates. In 1865, she dropped her letters to John Bunting, her old flame, into the Atlantic Ocean. “Destroy this unread,” she wrote years later into her diary from 1868–1869, when her greatest good friend’s engagement led her to ponder demise.

In different phrases, if she destroyed it, it’s most likely fairly juicy.

So it’s important that her writing about Scott is rife with redactions. She tore out the web page of her diary instantly previous her first point out of Scott. Sections from pages overlaying April 1866, when Scott spent days touring simply to go to her and the 2 declared their love, and June and July 1866, together with the day of Scott’s birthday, are neatly excised, as if reduce out with scissors. Generally she reduce out solely his title, nonetheless evident by context clues.

I do know these occasions occurred as a result of she wrote about them later. However I understand how a lot they meant to her as a result of she eliminated the proof.

For that cause, I’m glad I first learn her diaries in bodily type, the place I seen the alterations instantly. They’re a lot much less obvious, a lot simpler to overlook utterly, in digital type. How are you going to decide that pages have been eliminated when solely the pages themselves are digitized? How are you going to even start to determine what was on these lacking pages should you don’t know they existed?

So, was it mistaken to advocate for these papers to be digitized?

After all not. In-person analysis presents important limitations to entry, and bodily archives aren’t full both. Nevertheless it’s value remembering that paperwork are objects with their very own materials lives, usually not reproducible by expertise.

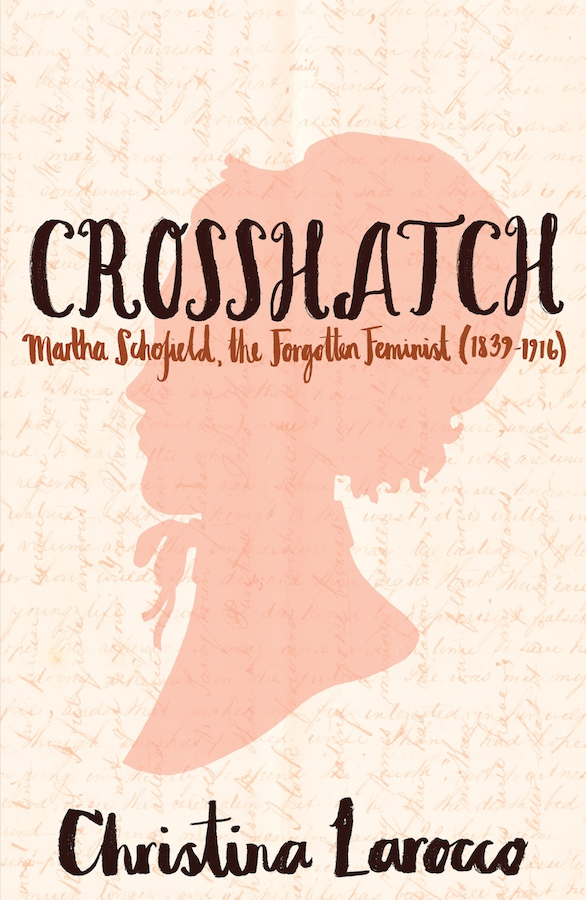

Author, e book coach, and historian Christina Larocco’s newest e book, Crosshatch: Martha Schofield, the Forgotten Feminist (1839–1916), is now obtainable for preorder. This March, she’s giving freely 31 free writing technique periods to nonfiction writers who love to assemble info however typically get caught in analysis rabbit holes. Seize your free session right here.

Christina Larocco is a author, Creator Accelerator–licensed e book coach, and historian who focuses on mixing the educational and the artistic. She is the creator of The Ladies’s Rights Motion since 1945 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022) and Crosshatch: Martha Schofield, the Forgotten Feminist (1839–1916) (Blackwater Press, forthcoming). As a e book coach, she helps writers who combine analysis into artistic and business nonfiction dig themselves out from beneath their mountains of data, discover the throughline of their e book, and reclaim their authority as a author in order that they’ll write a e book that, whereas informative, is a lot greater than a group of info—it’s a murals. Go to www.christinalarocco.com to be taught extra and to contact her.

0 Comment