Man of the West: Akutagawa’s Tragic Hero

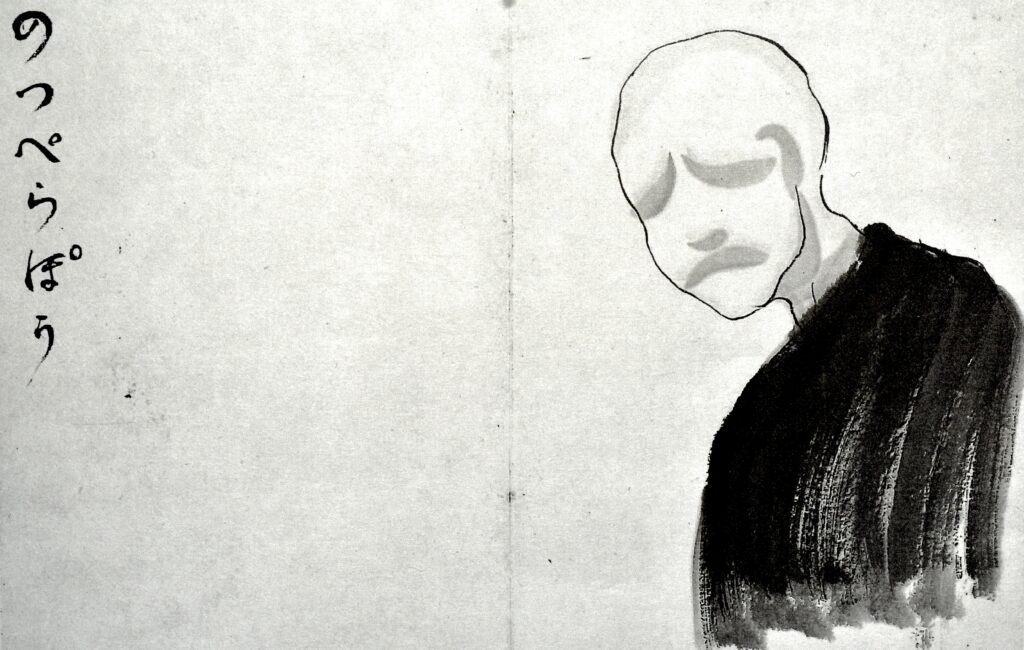

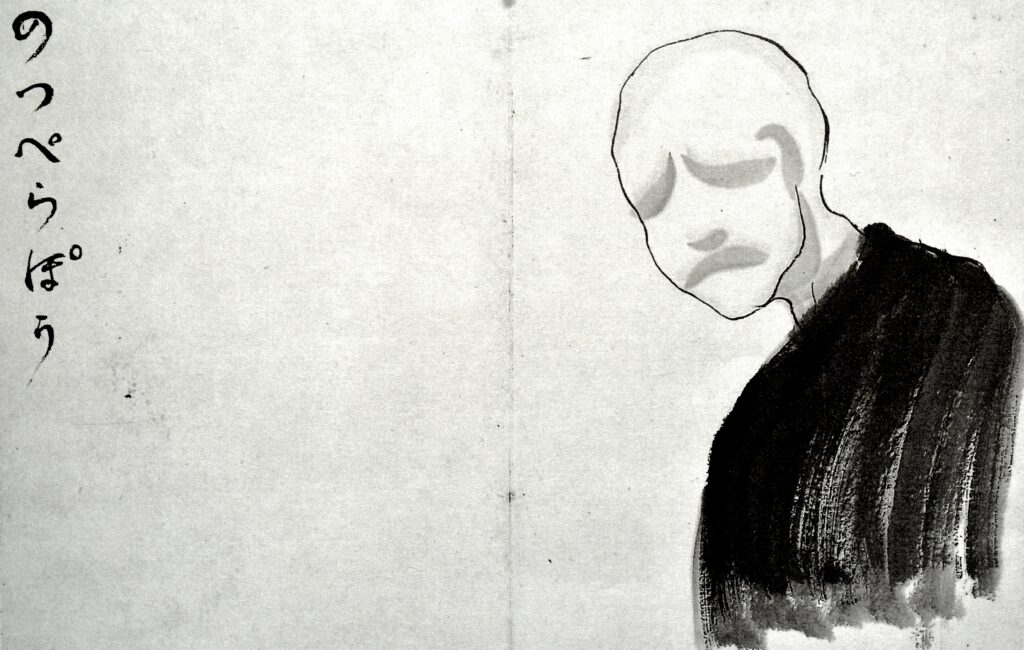

A drawing of the Noppera-bō by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, through Wikimedia Commons. Public area.

On the night time of July 24, 1927, Ryunosuke Akutagawa swallowed a deadly quantity of Veronal, slipped onto a futon beside his spouse, and fell asleep studying the Bible. The author was thirty-five years outdated. Proclaiming himself an atheist but preoccupied by Christianity, he had written, shortly earlier than his suicide, “Man of the West,” a sequence of fifty aphoristic vignettes during which Jesus Christ is an autobiographical author who has profound perception into all human beings however himself. Akutagawa was a prolific and celebrated author and one of many first fashionable Japanese writers to realize reputation within the West. He was drawn to the son of God at a time when he suffered from visible and aural hallucinations, usually accompanied by migraines. His spouse generally discovered him crouched in his examine in Tokyo, clinging to the partitions, satisfied they had been falling in.

Days earlier than he died, Akutagawa wrote a sequence of letters to his household and pals. At a crowded information convention the day after Akutagawa’s suicide, his buddy Masao Kume learn aloud a letter addressed to him, “Be aware to an Previous Good friend,” generally known as Akutagawa’s suicide observe. The letter describes, in darkish comedy, the sensible banalities that undignify the grandiosity of arranging one’s personal demise: issues involving the rights to his work and his property worth and whether or not he’d be capable of maintain his hand from shaking when aiming the pistol to his temple.

Additionally it is a portrait of the creator’s interiority in his remaining moments. “Nobody has but written candidly concerning the psychological state of 1 who’s to commit suicide,” the observe opens. “In one among his brief tales, [Henri de] Régnier depicts a person who commits suicide however doesn’t himself perceive for what purpose,” he writes. “Those that commit suicide are for probably the most half as Régnier depicted, unaware of their actual motivation.” Just like the Christ-poet of his fiction, Akutagawa thought he may see into the souls of all males—besides his personal. Maybe he couldn’t look; maybe he didn’t wish to, for the place there’s motivation, there’s culpability: exactly what he needed to abdicate in demise. “In my case, I’m pushed by, on the very least, a obscure sense of unease,” he writes as a substitute. “I reside in a world of diseased nerves, as translucent as ice.” He principally needed relaxation, he wrote. In “Man of the West,” he writes, “We’re however sojourners on this huge and complicated factor referred to as life. Nothing offers us peace besides sleep.”

***

Akutagawa was born in 1892 in Tokyo, fourteen years after town grew to become the brand new capital of Japan throughout the Meiji Restoration. His fifth story, “Rashomon,” revealed when he was twenty-two, heralded a pressure of rising expertise and went on to enter the canon of recent Japanese literature. Akutagawa wrote critically acclaimed tales, one after one other—“The Nostril” (1916), “Hell Display screen” (1918), and “Within the Bamboo Grove” (1921)—lots of them nonetheless taught in Japanese excessive colleges. Like Manet, who painted his French contemporaries sporting historic costumes in classical poses, Akutagawa usually took the characters of historic Japanese legends and reanimated them with a recent sensibility. He was viscerally unsentimental. In “O-Gin” (1922), he describes an orphan lady who, alongside along with her adopted Christian dad and mom, might be burned alive until they surrender God. The lady is the primary to surrender her faith, to not save her life however as a result of she is aware of it’s hell the place she is going to reunite along with her lifeless dad and mom. The narrator—Akutagawa at all times has a narrator, even in shut third individual—ridicules her as “the only most embarrassing failure.”

Akutagawa’s tales flourished throughout a time simply after the autumn of the Tokugawa shogunate, when outdated customs had been falling away to Western influences pouring right into a quickly modernizing nation. Fashionable Japanese literature flourished as a result of there was a strong tradition of literary magazines that revealed criticism, generally complete essays dedicated to a single brief story. The Japanese I-novel custom—autobiographical novels and brief tales that always combined narration with essayistic lyric—loved excessive acclaim with the bundan, a coterie of intellectuals, critics, and editors in Tokyo. Just like the French, who adored Tokugawa-era literature and artwork, Japanese publishing didn’t stake a significant distinction between autobiographical novels and memoir. The I-novel was mentioned to be inherently Japanese, relationship again to the zuihitsu of the medieval Heian interval, a style of autobiographical storytelling braided with lyric essay, verse, and literary criticism.

Very like modern autofiction, I-novel fiction usually hinged on a confession, notably unflattering, made by a narrator assumed to characterize the creator. The bundan praised fiction for a way unlikeable its protagonists appeared, which signaled a better danger by the creator—increased stakes. In Toson Shimazaki’s A New Life (1919), the creator’s stand-in discloses having intercourse along with his brother’s daughter. Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human (1948) follows a sociopathic misogynist, an outcast of society who’s locked up in an insane asylum.

Drawn to the status of the I-novel style at a time when historic fiction was more and more devalued, Akutagawa started, in what can be his late type, to experiment with autobiographical brief tales and private essays. All through these works, we encounter a younger man who’s humorous and self-possessed, erudite in a comic book manner, uncommonly sensible, and vulnerable to lust and ambition. In “The Lifetime of a Silly Man” (1927), the narrator feels a “ache near pleasure” after listening to that his mentor, the legendary Meiji novelist Soseki Natsume, has died. Concerning a cast-iron sake bottle with finely incised traces, he has an epiphany of “the fantastic thing about ‘type.’” By listening to The Magic Flute alone, he is aware of that Mozart was a person who, like him, had “damaged the Ten Commandments and suffered.”

Akutagawa’s suicide observe is preoccupied with sin and transgression. The author was “conscious of all of his faults and weak factors, each single one.” He apologizes vaguely, “I simply really feel sorry for anybody unlucky sufficient to have had a nasty husband, a nasty son, a nasty father like me.” From a few of his autobiographical tales, revealed posthumously, we all know that Akutagawa had an affair with the poet Shigeko Disguise. He believed the affair, as he disclosed in a letter to Ryuichi Oana, his frequent cowl designer, led to his suicide. In “Silly Man,” Shigeko is pseudonymized merely as “loopy lady” and characterised as a charismatic and harsh lady. “I’ve not tried—consciously, a minimum of—to vindicate myself,” he writes in a separate observe to his buddy Kume Masao. “But, unusually, I’ve no regrets.” What comes off the web page is guilt just for his lack of guilt. One will get the sense of Akutagawa talking out of either side of his mouth, of somebody each resisting and needing to admit, to problem a mea culpa on his personal phrases.

However from what, precisely, does Akutagawa want—or not want—to vindicate himself? Centuries of traditional Japanese literature, from The Pillow Guide (1002) to The Lifetime of an Amorous Man (1862), had already normalized the follow of adultery. A better sin could be discovered within the remaining traces of “The Child’s Illness” (1923), during which Akutagawa recounts his toddler son’s near-death sickness. Akutagawa admits that he had as soon as thought of writing a sketch about his little one’s hospital keep however “determined towards it due to a superstitious feeling that if I let my guard down and wrote such a bit, he may need a relapse. Now, although, he’s sleeping within the backyard hammock. Having been requested to write down a narrative, I assumed I’d have a go at this. The reader would possibly want I had accomplished in any other case.”

Akutagawa’s transgression is the act of writing itself, writing that takes struggling as its topic. Akutagawa allegorizes the sadomasochistic need to inform tales about ache in his masterpiece “Hell Display screen.” It tells the story of a Heian painter who can paint solely from life. To color a scene of individuals burned alive, the emperor arranges to have somebody burned in entrance of the artist’s eyes. The painter agrees, however it is just throughout the burning when the emperor, smiling, shocks the painter by sending the artist’s personal daughter, sure to a carriage, burning in flames. He watches in horror, then radiance—“the radiance of non secular ecstasy.” His completed portray, the hell display, is lauded by critics. The artist hangs himself.

The painter reaches his breaking level for the time being when he confuses his life’s realities with artwork’s imaginaries. This can be a widespread theme in Akutagawa’s I-novel writing. Within the posthumously revealed “Spinning Gears” (1927), the narrator, Mr. A., turns into satisfied that pages from The Brothers Karamazov have been stitched into the center of a duplicate of Crime and Punishment—presumably a hallucination. In his sight view, he begins to see semitransparent wheels, spinning and multiplying, just like the eyes or wings of the angel within the ebook of Ezekiel. “I opened my eyes, and shut them as soon as once more as soon as I had confirmed that no such picture existed on the ceiling,” he writes.

Born to a “lunatic” mom, Akutagawa was afraid within the years earlier than his demise that he, too, would lose the flexibility to inform what was actual and what was not. Maybe all autobiographical writers expertise the second when the creativeness of their recorded recollections begins to overwrite what truly occurred. Akutagawa’s story “Daidoji Shinsuke: The Early Years” (1924), advised within the third individual, consists of the memorable line: “He didn’t observe folks on the road to study life however somewhat sought to study life in books with a view to observe folks on the streets.” At first was the phrase. Right here was a author who may now not distinguish between actuality and the confabulations of his personal thoughts.

***

For Aristotle, the tragic hero’s heroism carries the seeds of its personal destruction: the tragic flaw. The tragic hero of Nietzsche’s The Delivery of Tragedy (1872) possesses no flaw in any respect, solely an inhuman, semidivine surplus that requires him “to do penance by struggling eternally.” Nietzsche’s affect on Akutagawa, of which the latter wrote usually, is especially legible on the finish of his life. In “Man of the West,” there are, along with Christ, many different “christs,” incarnated in writers like Goethe and Walt Whitman. For his or her poetic temperament, these poets should endure, like Christ, a “darkest, most desolate hour,” for “sentimentalism is well confused with the divine.” In his suicide letter, Akutagawa writes: “I’ve seen, liked, and understood greater than others. This alone grants me some measure of solace within the midst of insurmountable sorrows.” It’s his godlike capacity to see, love, perceive greater than others that constitutes his mortal transgression. The postscript to the letter reads: “Studying the lifetime of Empedocles, I spotted what an historic need it’s to make oneself a god.”

By the top of his life, Akutagawa was now not the artist watching his daughter burned alive; he was within the burning. In “Spinning Gears,” Mr. A. leaves the Imperial Lodge, the place he writes, to stroll in limitless circles round Tokyo, again and again, like Dante’s damned. “I had sensed the inferno I had fallen into.” Solely a author as conflicted as Akutagawa—struggling between sensitivity and indifference, mental distance and delusions of the grandeur of his personal ache—may successfully sensationalize his personal psychological sickness because it was occurring. Akutagawa’s craft was unparalleled in his era. Right here was a younger man whose expertise had accelerated past his personal capacity to grasp it, a lot much less management it.

A disordered thoughts: this affliction that so usually seems in tales has, since antiquity, been despatched by the gods. (No less than as early as “The Bacchae,” of 405 B.C., Dionysus casts a vengeful spell of insanity upon your complete metropolis of Thebes.) “I used to be in hell for my sins,” Akutagawa writes. “I couldn’t suppress the prayer that rose to my lips: ‘Oh, Lord, I urge thy punishment. Withhold thy wrath from me, for I could quickly perish.’” On this planet of literature, Akutagawa “found his personal soul, which made no distinction between good and evil,” as he wrote in “Daidoji Shinsuke.” “I’ve no conscience in any respect,” he writes in “Spinning Gears.” To him, writing is amoral, has no compass apart from the aesthetic, which is its transgression.

***

Every time I learn “Be aware to an Previous Good friend,” I see a distinct individual. I see a person convincing himself he’s a god, or a god convincing himself he’s human. I see somebody who suffered a ache past empathy, resistant to empathy. He fantasized about suicide the best way folks watch TV. A delicate man distracted by his items of knowledge, he resisted the compassion of others as a result of he had no compassion for himself. He numbed his concern with mind, mistook self-pity for humility. He needed to be forgiven—however by no means to apologize. He believed his personal self-mythology was a public service.

His solely happiness was within the mundane particulars of on a regular basis life. Yasunari Kawabata, the primary Japanese author to win the Nobel Prize, quoted, in his 1968 Nobel Lecture, a passage on the finish of Akutagawa’s suicide letter:

If we are able to submit ourselves to that everlasting slumber, we are able to doubtlessly win ourselves peace, if not maybe happiness, however I had doubts as to once I can be courageous sufficient to take my very own life. On this state, nature has solely change into extra stunning than ever to me. You’re keen on the fantastic thing about nature, and would little question scoff at my contradictions. However nature is gorgeous exactly as a result of it falls upon the eyes that won’t respect it for for much longer.

Right here, we discover an articulation of the Japanese notion of mono no conscious, the notion of magnificence exactly on the revelation of its transience. Having determined to finish his existence, Akutagawa begins to see clearly the fantastic thing about each prior second in his life, simply earlier than its extinction. The issues of this world are revealed as stunning as a result of magnificence is however a masks, nevertheless skinny, for the void that constitutes its which means. Is that this why he didn’t belief the sweetness that grew to become seen solely after his resolution to kill himself?

Akutagawa may need felt a tremor of the spirit that he believed may very well be pacified solely by merging with the void. There’s nothing all too particular about that. Generally, you’ll be able to see the void behind the snow falling on the river from the window of a subway automotive crossing the Williamsburg Bridge. You both make peace with it otherwise you don’t. You may acknowledge the void, clutch your coronary heart, squeeze your eyes closed, say your gratitude checklist, after which go on together with your commute. Most of us understand how to do that. We do it every single day.

Geoffrey Mak is a queer Chinese language American author whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, the Guardian, and Artforum, amongst different publications. He’s cofounder of the studying and efficiency sequence Writing on Raving.

0 Comment