Motherhood, Writing, and Making a Residing: A Dialog with Rosalie Moffett, by Kathryn Savage

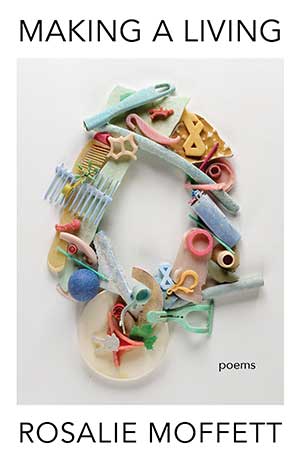

The surplus of capitalism is the backdrop in Rosalie Moffett’s Making a Residing (Milkweed, 2025), and on the foreground: motherhood, debt, forest fires, and a speaker who’s deep down like everybody “obsessive about dreaming / up the long run, with hell, with all / that spares us.” All through Moffett’s third poetry assortment, the sacred and the mundane collide because the speaker negotiates being pregnant and early motherhood amidst the economies and needs that form a Midwestern home life. Forsythia blooms outdoors the DoubleTree Inn. On the display screen of the Doppler climate app, need “rises, scatters.” Moffett’s poems maintain house for omens and prophecies, taxes, prenatal nutritional vitamins, and longing that unfolds like a “pocketknife.” Moffett, a former Wallace Stegner Fellow from Stanford College and assistant professor on the College of Southern Indiana, is deeply within the methods poetry can uniquely take into consideration time and the methods that form modern life. We mentioned her poetic consideration of search outcomes, 401Ks, and the advanced feelings of passing on this troubled world to a brand new era. In Residing, hope isn’t a far cry from violence, and evocations of magnificence go together with banality. “What then will I grow to be? Above the / new Costco, skeins of geese strung throughout the sky. On the / show of low cost flat-screens, extra sky.”

Kathryn Savage: In what methods does Making a Residing go together with your earlier works of poetry, Nervous System and June in Eden?

Kathryn Savage: In what methods does Making a Residing go together with your earlier works of poetry, Nervous System and June in Eden?

Rosalie Moffett: In every of those books, what I’ve ended up doing, generally from wildly totally different angles, is attempt to discern how we come to assume we all know a factor and to plot the boundaries of what may be recognized. So, I find yourself wanting on the forces of authority at work: science and historical past and religion, and likewise the way in which language itself operates on our pondering.

In Nervous System, I used to be drawn right into a poetic reckoning with my mom’s signs of aphasia, weaving in neurological analysis and delusion and etymology. In that guide, in addition to June in Eden, I used to be pondering carefully concerning the intrinsic relationship {that a} poem’s line—breaking off, because it does, right into a clean house—has to the unknown, the way it revels in making the thoughts conscious of those clean areas, and conscious of the necessity to cross them, again into what’s knowable.

And in Making a Residing, that clean house is the long run, a website that was prolonged for me by the will to have a baby. That is an expanse that’s commodified, is preyed on and profited from, is probed by medical procedures whose purpose is to diagnose its potential holes. This future is ratcheted into the current by predictive-text, by search outcomes primarily based on previous shopping for conduct, and padded by 401Ks and mortgages. Items of the long run are being purchased and bought, piecemealed into stock-market ticker symbols. So, within the guide, I’m that: how to consider the long run, given our current, how to think about it, given a baby.

Savage: All through Making a Residing, a McDonald’s or Costco seems in poems with titles like “A Prophecy” and “Omen.” I used to be on this adjacency; what’s the stability you search to strike in your work between the sacred and the mundane or profane?

Moffett: I’d wish to place every, in my poetry, to set the opposite in some form of aid. And, to present a way of what sort of impulses are at work in me, I assumed, typing this: aid? The phrase out of the blue unusual and multivalent in my thoughts. And the etymology lets me realize it comes from the French, relever, to re-lift—i.e., the sense I meant: to elevate up the sacred, to let it’s discerned from the profane, and vice versa—however the entry additionally states that the phrase was used earlier in English as “that which is left over or left behind” and likewise as “feudal cost to an overlord made by an inheritor upon taking possession of an property.”

There are histories haunting what we are saying, which implies they hang-out how we predict.

So, like so many phrases we use, blithely, there are histories haunting what we are saying, which implies they hang-out how we predict. Surprisingly typically, these ghosts reveal the overlap between cash and the metaphysical, the profane and the sacred. This elements in a number of occasions in Making a Residing, as I take into account, for example, mortgage, which comes from demise pledge, redeem from bribe, blessing from wound. So, maybe, one purpose within the guide—which I strategy with a sure stock of picture, with metaphor and juxtaposition—is to grow to be conscious of those overlaps, to see by the murk to inform what’s prayer, what’s commerce.

Savage: I observed “hope” is the title of three poems. How does Making a Residing maintain house for hope?

Moffett: I believe the guide holds house for hope the way in which the stack of firewood in “Omen” holds house for the invasive ash beetle: it might’t hold it out, and what it does is perhaps referred to as lovely and is perhaps referred to as harm.

And, just like the beetle, an understanding of the character of hope bores in by the cracks between poems. “A Prophecy Is Nothing” ends with “the multitude self-populates / with algorithmic precision what it thinks / you’ll need. What may match greatest as bait.” The subsequent title is “Hope.” The longer term baits us, like deer to a salt lick, with hope. It’s so lovely and glittering, it’s so essential to our survival as we enter the clearing—

And right here I’m, right here we’re, blinking within the daylight. Who would step into the long run with out it, given all of the proof within the current?

Savage: Within the poem “Forsythia,” the speaker weaves collectively the previous, current, and future. “There’s the current the place everybody lives, now / studded with moments I’ve robbed from a time / I think about, by which a baby watches me scavenge / the panorama for bits of magnificence, / learns easy methods to do it herself.” I’d love to listen to you talk about the transitory, in relationship to nurture.

Moffett: Lately, late to the social gathering, I received John Berger’s About Wanting, and occurred to crack it open to a web page on which I learn, “Reminiscence implies a sure act of redemption. What’s remembered has been saved from nothingness.” Surprisingly, I believe I can say that reminiscence and hope share lots of qualities. They’re each inaccurate, untrustworthy, damaging, and exquisite—and so they save us from nothingness.

I typically argue that poetry can take into consideration time in a means nothing else can, partly by what I name the tesseract of the road, which may transport us by nice distances, which may trick us, virtually, into the form of large-scale perspective that we as a species appear to battle with (see: local weather change.) This catapult of time and scale is one thing I’m aware of, and courting, particularly within the poem “Hysterosalpingography” the place the “wiggle room” of historical prophecy turns into the examination room for our present-day medical auguries, the place the fundus of the attention or uterus is made to increase wildly, turns into the sky.

Generally, as I work on a poem, I consider every time I press the “return” key as an experiment I conduct on myself: will my thoughts make the leap? Will it cross this distance? How a lot not-knowing can I deal with, and when will what I’m asking it to assemble—what the world can maintain—be an excessive amount of? My expertise of getting my daughter has posed these identical questions.

How a lot not-knowing can I deal with?

Savage: All through Making a Residing, I observed a number of titles repeat, and eager consideration can also be paid to prophecy. How does repetition relate to the unknown and anticipated?

Moffett: Sure, I like the connection between titling—and repetition of titles—and prophecy. It comes, partially, from a suspicion of certainty. You flip to the desk of contents as a navigational software for what’s forward. A prophecy or omen, identical. However repetition troubles that logistic: hope? which hope? which redemption? What appears to be an providing of navigability, of predictability, is undone as you progress by the guide. Even the trick I like, of a title bleeding into the primary line, has a destabilizing feeling: you thought you had been on the door? You’re already inside. What appeared the start reveals itself as the center. Within the poem “Time and Place,” every sonnet finish devolves, you would possibly say, again to being a center.

So, as a result of I’m not prophetic, what I supply is what it does to me, what it does to us: the relentless need to achieve into the long run, our relentless failures to do something extra however hold marching into it, second by second.

Savage: I cherished how the poem “A Prophecy Is Nothing” means that success and loneliness are twined. “It’s really easy as of late / to obtain what you thought / you wanted whereas in evening’s emporium / of urgencies.”

Moffett: Oh, I believe shopping for issues exacerbates loneliness. And when the algorithm is doing its factor: feeding us services and products, the way in which a great good friend listens, watches, is aware of simply what to get us for our birthday, isn’t there a way, momentarily, that we aren’t alone?

However then, in fact, there’s an epidemic of loneliness, and Amazon is richer than many nations. Moreover, Amazon hosts Ring as its subsidiary, which operates one thing referred to as Neighbors, which is a “hyperlocal social networking app” that permits customers to “anonymously talk about crime” and supply footage to regulation enforcement. So, even the folks closest to one another may be made faceless and suspicious, for a price.

Savage: Poems equivalent to “Complete Legal responsibility” measure prices. Insurance coverage, mortgages, and indebtedness seem all through the guide. How do the calls for of capital inform your poetics?

Moffett: The calls for of capital form virtually all the things—they form my time, my consideration, my power, in order that they have a bearing on my poems, that are comprised of my time, my consideration, my power.

As you would possibly guess from my reply re: loneliness, it appears clearer to me day by day that our capitalist (violent, ruthless) tradition is self-alienating, is a barrier to tenderness, to happiness. A beautiful poet provided me this recommendation on an early, extra bitter draft of Making a Residing: It wants extra emotional intimacy. This remark revealed to me how the alienation of consumerism had suffused my writing about consumerism, and the hassle required to permit sensitivity and vulnerability to come back again into the poems. As a result of in the end that urge—a bitter, indignant cataloging of American absurdities, a form of poetic gripping of the reader’s shirtfront and yelling Look!—is linked to sensitivity and vulnerability.

I at all times inform my college students that one of many beauties of poetry is the way in which it permits us to show again to our lives with heightened consciousness, with new eyes. For me, the arc of the guide is towards this consciousness: the power to inhabit this place—America, English, capitalism—with out numbing ourselves to it with our screens and consumerism, with out wanting away.

One of many beauties of poetry is the way in which it permits us to show again to our lives with heightened consciousness, with new eyes.

Savage: On vulnerability, being pregnant is mapped onto the web page. I ponder if the guide traces gestational age? In the event you take into account it to be chronological?

Moffett: I wished to withstand the chronological arc—however I couldn’t. I wished to maintain the arrival of my daughter out of the guide, however couldn’t. And bringing her in made it simpler to maneuver the poems towards tenderness, to loosen my grip on the shirt of the reader. Narrative is , in fact, in consequence—consequence requires time. And, regardless of my lyric sensibilities, I suppose I can’t escape that.

Savage: Within the introduction to Artwork Monsters: Unruly Our bodies in Feminist Artwork, Lauren Elkin observes: “As I started scripting this guide, I turned pregnant with my son, and my curiosity in a feminist artwork of the physique turned particularly involved with how the physique speaks. . . . There was one thing new and low in my physique, rumbling and trembling and twitching, with a brand new relationship to gravity.” Tenderness, gravity. Would you wish to say extra on how motherhood informs your poetics?

Moffett: The formal sensibility and ethical sensibility of my work in progress could be very influenced by motherhood. I’m at work on a collection titled “To Hear a Conflict from Far Away” (which pulls its title from Etel Adnan’s “To Be in a Time of Conflict”), and within the collection kind, I’m making an attempt to seize the profusion of moments that make up motherhood, whereas permitting the rawness of it, the privilege and gentleness of it, to be struck by a consciousness of atrocity, of the continuing genocide in Gaza. As soon as, whereas driving to show, I felt my milk let down after I heard the cries of a ravenous child on NPR’s protection of the famine in Gaza.

I’ve been conscious, as I work on this, of how my effort to know “how we come to assume we all know a factor” turns into a distinct form of work now. What distances is the thoughts unable to cross, to shut? What mechanisms (of concern, of sensitivity, of rhetoric, of id) restrict my capability to understand the magnitude of this atrocity? What sort of poem can I write as an American mom at the moment?

0 Comment