The White Shirt of Sandra Mozarowsky

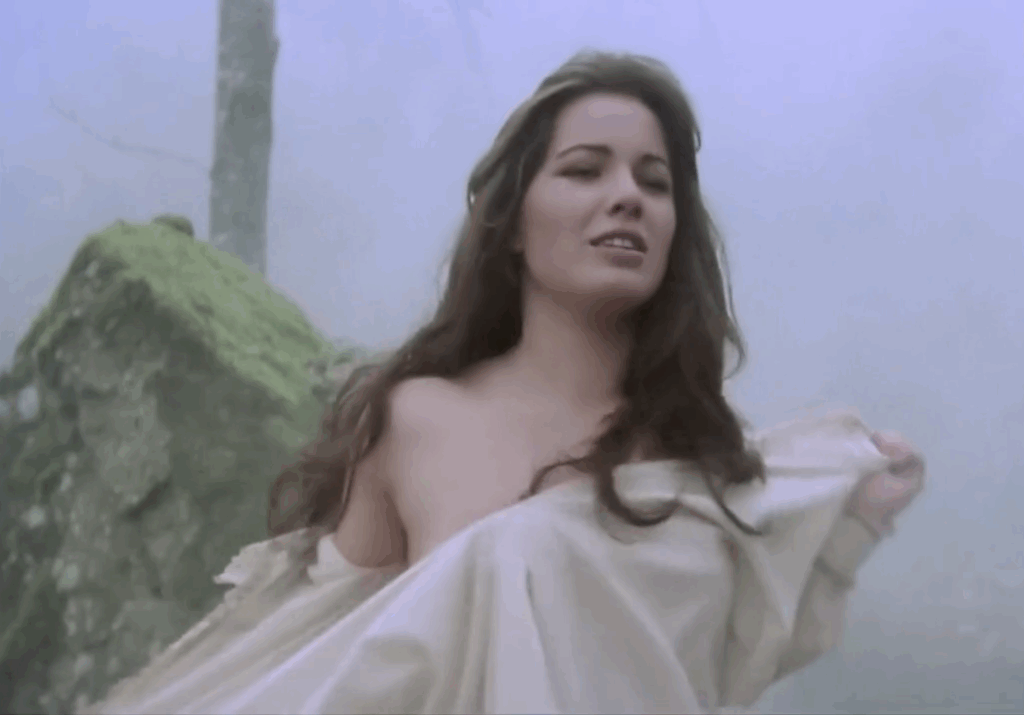

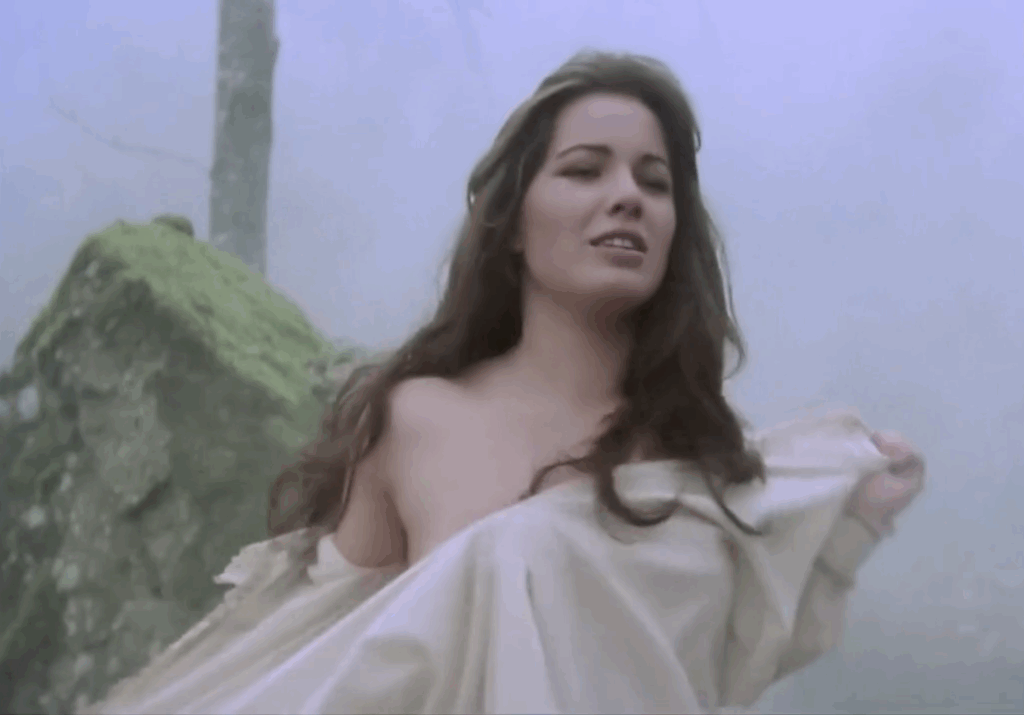

Mozarowsky in Beatriz (1976), directed by Gonzalo Suárez.

For hundreds of years, philosophers, theologians, and poets have pursued the which means of life. Is there one, and, in that case, what’s it? Spirituality? Faith? Ask a person on the road the which means of life and he may simply say “Surviving.”

However ask a teen, and also you’ll get your reply. She’ll let you know the which means of life is Love, and her certainty ought to make you content for her. By twelve, I’d fallen in love greater than fifteen occasions. My romances had been large, earth-shattering, way more devastating and intense than any of those that got here later. All the boys had been excellent, being imaginary, and since I noticed no want for messy breakups, we all the time ended issues on good phrases.

After I was six or seven, our babysitter entertained us with fairy tales. She all the time informed the identical story. As soon as upon a time, in a faraway land, Pablo (my brother) married a princess and have become king. Blanca (my sister) wed the crown prince of the nation subsequent door, which meant she, too, was in line for a throne. I all the time received the prince’s youthful brother, which meant contenting myself with being a princess—and I used to be not content material. Who can be? In my creativeness, I stole my sister’s boyfriend.

Sandra Mozarowsky was by no means a queen. She was by no means a king’s girlfriend. She was the king’s lover, although, should you consider the rumors.

Because the Franco regime approached its finish, its topics began demanding freedom of expression. Not the entire nation, however sufficient of us to be heard. Our calls for for liberty received louder and extra insistent, and the regime took them to imply that we wished to see breasts. We wished bare ladies, or half-naked, and so we spent the mid-seventies gaping in awe as our nation attained the doubtful freedom of a nationwide cinema starring ladies who, with out fail, opened or eliminated their tops inside seconds of showing onscreen.

Sure, in Spain, freedom was for breasts. You may spy some liberated bush in a semilegal softcore journal, too, although by no means ever a penis. Seen male genitalia can be libertinism, which was anathema. In line with the numerous authorities ministers and functionaries assigned to disseminate this message, liberty was one factor, libertinism one other, and as a nation, it was essential for us to not get them confused.

As a nation, we had been ready for Franco to die. A few of us had been keen and excited; some had been fretful and afraid. A few of us staged strikes and demonstrations that had been met with ferocious police repression. In his sickbed, the dictator signed his final loss of life sentences with a decisive, if shaky, hand. All the remainder of us sat and watched destape.

Destape, which suggests “undressing,” was the identify we gave our new erotica. We had been such innocents, or such pigs, that we actually did assume all these tits meant democracy and freedom, or, on the very least, an uplifting promise of each.

Sandra Mozarowsky was a destape actress, however earlier than that, she was a lady. She was one her entire life, actually: she died at eighteen. She was born in Tangiers in 1958 (three years earlier than me), the third and youngest youngster of a Russian father, Boris, and Spanish mom, Charo Ruiz de Frías. In 1961 the household moved to Madrid, the place Sandra studied on the British Faculty and, in response to a chunk within the October 1, 1977, problem of ¡Hola!, “started to display her creative items, particularly in dance, distinguishing herself as an impressive ballet pupil.”

At ten, Sandra made her display screen debut in El otro árbol de Guernica, which, she defined in an interview, was simply luck: a pal of her mom’s occurred to say her to the director, Pedro Lazaga. She waited solely 4 years to “get again in entrance of the digicam,” as she put it, in Lo verde empieza en los Pirineos, which stars José Luis López Vázquez as a Spanish hick with a serious problem—any time he meets a lady he likes, he involuntarily tanks the attraction by imagining her with a beard. He goes to a psychologist, who reveals a childhood trauma that prompted his compulsive inhibition with ladies, then reminds him that males are the kings of creation, ladies their lesser helpmeets.

“Any more,” the shrink instructs, “earlier than you go as much as a lady, repeat to your self, ‘She’s inferior to me.’ ”

López Vázquez and his buddies plan a visit to Biarritz to see horny films, like Final Tango in Paris. Pre-destape, when something attractive was banned in Spain, our columnists and speaking heads hotly debated the road separating erotica from porn. On the one hand, it was a serious controversy, however on the opposite, all of us knew erotica was tasteful, it was artwork, and porn was neither. Regardless, you couldn’t see both in Spain. Nudity was a no-go, and so we poured into Biarritz and Perpignan on the weekends to see every part the generalissimo, in his knowledge, had chosen to censor. Heading house, we felt very free and complicated. We’d seen nipples! Pubic hair, too, and a silhouetted hard-on. We’d even seen half a ball.

I, too, went to Perpignan to look at porn. I’ve no reminiscence of who drove, who else was there. Grown-ups, presumably. I used to be fourteen, and all I bear in mind is that Emmanuelle was bought out and we needed to content material ourselves with some unusual film, practically all intercourse, that almost bored me to tears. I solely shunned napping as a result of my true purpose wasn’t simply seeing the film however describing it—i.e., bragging—to my classmates.

When López Vázquez and his buddies arrive, they uncover that Biarritz is swarming with Spaniards. Not a single automobile has French plates. Spanish buses idle en masse outdoors the theaters. All of Spain has descended on Biarritz to look at what we used to name blue films. Our heroes, in fact, are delighted, particularly since, pretty much as good Spaniards, they’ve by no means bothered studying any language however their very own. Publish-beach, our three hicks shut themselves up in a theater, watching the identical film on repeat, gaping at each nipple and thigh. Sandra seems very briefly, as a “younger French woman” who sits with our protagonists on the cabaret they go to after lastly staggering out of the theater. She and her two buddies are cute and younger, the Spaniards previous and ugly, however the ladies nonetheless wish to sleep with them. (Unsurprising on this model of actuality, which holds that Spanish males are irresistible and French ladies are sluts.) Sandra, fortunate woman, will get López Vázquez, who might be not simply her dad however her grandfather. She offers him her most charming smiles, her most seductive green-eyed appears to be like, however when he tries to kiss her, the curse strikes. An enormous, darkish beard sprouts from her face, and he recoils in worry. After that, a showgirl hauls him on stage—in drag? In a duck costume? I can’t bear in mind. I turned the film off as quickly as Sandra’s scene ended. I used to be solely waiting for her.

***

When she was sixteen, in 1974, she made her horror debut in El mariscal del infierno, starring Paul Naschy (born Jacinto Molina Álvarez) as a villain based mostly on the medieval serial killer Gilles de Rais. Sandra performs a anonymous virgin whom he sacrifices so he may give her blood to an alchemist who’s promised to make use of it to make him a sorcerer’s stone. Sandra’s character has no strains, which occurred to her so typically that she picked up the identical strategies as a silent movie star. On this function, she’s tending crops when Paul Naschy’s henchmen kidnap her. She will get dragged into his lair, the place she cowers in her white shirt, screaming in horror as he rubs himself towards her, rips her prime, grabs her breasts. She faints at exactly the fitting second and wakes in a cover mattress with Paul Naschy thrashing on the bottom beside it, having an epileptic seizure (Sandra, terrified, screams some extra).

Subsequent, the director takes us outdoors the citadel. Sandra, gagged and shrouded in crimson, lies certain on an altar, ready for the knight’s spouse, a harpy with painfully overplucked eyebrows, to slit her throat. Our villainess is sporting a wierd gown, lengthy and slender, with an infinite collar and swinging sleeves, paired with slightly conical hat like stewardesses wore again then. Total, the impact is hippie-medieval, very sixties kitsch.

Sandra does, certainly, get her throat slit. She writhes whereas it occurs, breasts bouncing, large. She’s silenced by the gag, however panic transforms her face because it did in practically all her roles: Sandra as sacrificial lamb, damsel in misery, tied up and murdered by one monster after the subsequent.

Sandra Mozarowsky was stunning. She had a Slavic face: large inexperienced eyes that tipped up on the corners; large, plush mouth; pale pores and skin; a lot straight, shiny chestnut hair she may have starred in shampoo commercials. Would have, if she hadn’t died too younger to get really well-known. In an previous problem of Pronto, I noticed her described as a “girl-woman who broadcasts sexiness and innocence on the identical time … inexperienced eyes, excellent options, and a statuesque physique—although she’ll must watch out to not get fats.” An exaggeration, that final bit. Sandra wasn’t skinny, and she or he did placed on weight simply, however nobody cared about that, given her age, magnificence, and gameness to take off her garments each time a script referred to as for it—which was all the time, each time.

One individual did care about Sandra’s weight: Sandra herself. Weight-reduction plan was one of many obsessions of her brief life. She’s half-naked in lots of the photographs I’ve seen of her. In a single, her hair spills over her breasts, protecting them, as if she had been Girl Godiva. In one other, she’s wanting sleepily on the digicam, mouth ajar, an embroidered vest simply barely protecting her nipples. In a 3rd, she’s on her knees in a bikini, fingers behind her again, pouting suggestively on the digicam. And a fourth: Sandra taking (or ripping) her white shirt off, one shoulder already bared. A faint halo appears to encircle her, like a cloud drifting away. She appears to be like, unsettlingly, equal components virgin and whore.

Sandra got here from a conservative, middle-class background, and I doubt her mother and father had been thrilled about their youngest daughter’s burgeoning profession as a destape star. In an interview with Primera plana, Sandra says, “For 4 years, my mother and father had been towards my appearing. Slowly, although, I satisfied them to let me do it so long as I may stability it with college.” In a brief interview she gave the journal Diez minutos in July 1975, as a part of the press tour for Las protegidas, her father’s supposed opposition to her appearing got here up once more. Requested if she “linked” to her function as a prostitute, Sandra says, “Effectively, it’s difficult, however I simply tried to do not forget that the character’s new to the job, and enthusiastic about it.”

Sandra comes throughout as impartial, an individual of character, as she preferred to say. She was solely sixteen in July of 1975. Franco hadn’t died but, Spanish society was Catholic and repressed, and but she managed to earn a pleasant residing appearing in films that scandalized her household.

In that very same problem of Diez minutos, I encounter a distracting story. It’s a scoop—exclusive!—titled, “Romeo and Juliet in ’75.” On the quilt, we get a style: “Meet the lovers whose destiny broke Italy’s coronary heart! Earlier than throwing themselves below a practice, they left us their final phrases on tape …”

Our Juliet, Maria, was born within the city of Rapolla. She died at seventeen. We don’t get her final identify, solely that of her Romeo, Michele Gastoni, a nineteen-year-old from close by Melfi. We see them in black and white: Juliet (Maria) is a candy, scared-looking woman, Romeo (Michele) a resolute youth with skinny lips and one of the crucial egregious haircuts I’ve ever seen, a dense curve of hair clamped over his slender face.

After introducing the couple, the author describes Basilicata, the area the place they lived. Apparently, distress and poverty are endemic there. Maybe that is meant to contextualize the appalling story that comes subsequent. Our two lovers dedicated suicide by mendacity on railroad tracks. Each night time, the final practice arrived in Melfi at 11:45, having handed by the close by Tunnel of the Seven Bridges at prime pace. On the day they died, the teenage couple spent over an hour at the hours of darkness tunnel, ready for the practice. Throughout that hour, they—principally Michele—mentioned goodbye right into a tape recorder, preserving their motivations for posterity.

“One, two, three,” says Michele. “In the event you’re listening, return this recorder to M— F—. He didn’t know why I requested to borrow it. And share this tape with the world. I’m sorry if it upsets folks, but it surely’s what I’ve to do. Life is shit. It’s too boring. Maria agrees. Maria, you speak.”

“No, no. I don’t wish to.”

“If my mother and father are listening, and my brother, don’t fear. It’s not your fault I’m killing myself. It’s society. You guys ought to go on together with your lives. Don’t bear in mind me. I’m gone, so why trouble? Overlook me. Maria, severely, it is best to speak.”

“No.”

“Okay,” Michele says, and resumes his broadcast, complaining that no person appreciates him or shares his beliefs. He assures the listener that he’s not taking the flawed path, and that it’s higher (“extra acceptable,” he says) to die than to flee life with medicine and so forth. Why ought to anybody be depressing for sixty or seventy years? he asks. “We will go away this life as a result of we all know the subsequent one is coming,” he says. “I do know the subsequent world will likely be an enchancment. Ours is shit! Maria, come on, speak.”

Maria’s sobbing. “What ought to I say?” she chokes.

“Say good day to somebody. Say goodbye.”

“Goodbye to everybody, particularly Mama. No, no. I can’t.”

“Why are you dying?” Michele asks. “What’s making you do that?”

“Plenty of stuff,” says Maria, nonetheless crying. “Society, folks …”

“We wish to converse, although it looks as if we don’t,” says Michele, and launches right into a livid denunciation of humanity.

In some unspecified time in the future, Maria interrupts. “I’m prepared to speak,” she pronounces, now not in tears. “I need everybody to know we actually considered this. We had been speaking about it for a very long time, going forwards and backwards, and this morning we determined. We’re not altering them now. Nobody understands us. Society can’t perceive anybody, which is why we’re all prisoners. So don’t cry for me, okay? I like you, Mama, Papa. I like my household. I’m chilly.”

“All proper,” he says. “Lights out.” We hear them preparing for the practice.

“Maintain on!” Maria calls. “The place are you going? You mentioned we’d go collectively!”

“We’re nobody,” Michele concludes. “However nobody else ought to must die like this.”

After that, the lovers lie quietly within the tunnel. On the tape, we hear the practice approaching, their breath, the locomotive whistling into the tunnel, the automobiles roaring on the tracks, the brakes shrieking, somebody shouting “A shoe!”

“Was it an individual?”

“A boy?”

“No, there’s a lady right here, however she’s lacking her head.”

I’m stunned {that a} tabloid like Diez minutos would run this story in 1975, alongside “Amparo Muñoz turns twenty-one,” which options photographs of our Señorita Universo blowing out her candles; “Why the identify Pérez issues”; “Jackie Onassis’s intimate secrets and techniques”; and “Within the solar with Patricia,” a colour centerfold wherein Patricia, who they describe as “Claudia Cardinale meets Sweet Rialson, with some Raquel Welch thrown in,” poses very severely in her bikini on a rock by the ocean.

Diez minutos’s transcript of the taped dialogue has a wierd narrative pull. Michele comes throughout as a resentful, boastful, domineering younger man, clearly the brains behind each the suicide and the recording. He scolds his mother and father for his or her poverty, his brother for his acceptance. He’s not a sympathetic narrator.

However Maria! Her loss of life hurts. She was an harmless, suggestible, infatuated woman, completely keen to undergo her shithead boyfriend. On the tape, she’s his echo, so admiring and obedient she let him speak her into suicide. She gave up her life for love. Pet love. She’d solely been relationship Michele seven months. Certainly if he hadn’t roped her into this loss of life pact, she’d have dumped him, or he her, leaving her upset, however alive.

How can a seventeen-year-old resolve whether or not life is price residing? How can she reject one thing she barely is aware of?

***

A number of months earlier than Sandra Mozarowsky died, an interviewer requested her, “What do you see in your future?”

“I by no means take into consideration my future. I imply, I can’t think about it. I’ve a tough time believing in tomorrow.”

“What’s your purpose in life?”

“Being remembered after I die.”

“Do you are concerned about loss of life?”

“I’m not there but, fortunately. I’m undecided we must always fear about loss of life, and anyway, I’m life like. You’re born, you get previous, and you then die. It’s the best way of issues. Why ought to I’ve an issue with it?”

So far as Sandra was involved, the which means of her life was clear. She was going to make her mark, be successful. I talked to an actor and an actress who labored along with her on completely different movies, they usually agreed: she was a pleasant woman with good manners, slightly shy, very bold. She wished to be a star.

I believe the foolish reply she gave the interviewer (whose query was equally foolish) hides an surprising knowledge. A philosophy, even: Since I haven’t died, how ought to I do know whether or not to be afraid of loss of life? She’s received a degree. What scares us about loss of life is its thriller. Not even the oldest or wisest individual can inform us what loss of life is like. Possibly which means we must always cease worrying about it a lot.

There’s nothing people love like a pit. We could also be frightened, however deep down, we’re drawn to the void. Stand on the sting of a cliff, and also you’ll see how optimistic loss of life all of the sudden appears. Possibly it’s thrilling; perhaps it’ll be a change of tempo. Our fascination with the issues we worry is the rationale we like horror films. Sandra starred in seven works of erotic horror: Los ojos azules de la muñeca rota, El mariscal del infierno, La noche de las gaviotas, El colegio de la muerte, El hombre de los hongos, Beatriz, and El espiritista. She made twenty films between fourteen and eighteen.

Camus writes, “The actor’s realm is that of the fleeting. Of every kind of fame, it’s recognized, his is essentially the most ephemeral. At the least, that is mentioned in dialog. However every kind of fame are ephemeral. From the viewpoint of Sirius, Goethe’s works in ten thousand years will likely be mud and his identify forgotten … Of all of the glories the least misleading is the one that’s lived.” In line with Camus, this implies actors are fortunate. An actor can succeed or not, but when he does, it occurs now. He doesn’t have to attend for posterity, which might be by no means coming. His artwork means he lives many lives, as many because the characters he performs. He’s nobody and everybody, pure look, so many souls jammed into one physique.

So Sandra Mozarowsky selected the perfect occupation, and, as if she sensed that she solely had a short measure of time on earth, she hardly wasted any of her hours on diversions and distractions. As an alternative, she labored like a mule, residing many lives by her characters. However oh, what lives! Almost all of them had been insufferable.

At sixteen, she received her first starring function, in El colegio de la muerte. It’s set in Victorian London, however you may inform it was shot in Spain: all of the exteriors are in Madrid and Toledo. Sandra performs Leonor, a surprisingly well-nourished orphan. Within the opening scene, we see her (in fact) principally bare, tied to the rafters of some type of dungeon, cowering as one of many mistresses of the orphanage the place she lives whips her. After the beating’s carried out, its perpetrator, Miss Colton, bans Sandra from seeing the physician who’s scheduled to go to the subsequent day. Sandra’s attractive inexperienced eyes nicely with tears: she’s secretly in love with the physician.

Each woman within the orphanage is gorgeous, like Sandra, and each single one lives in worry of the vile Miss Colton and her iniquitous boss, Miss Wilkins. Each are parched, extreme ladies with overplucked eyebrows, scraped-back hair, and excessive Victorian collars. From their sly expressions, we all know they’re the villains. We get to know just one different orphan, Sandra’s finest pal, performed by a really younger Victoria Vera. All of the others vanish—a funds problem, I’m positive. You’ll be able to inform that the film (which, to be honest, has its charms) was made on a shoestring. Its entire solid is Spanish, regardless of the English setting, and Dr. Kruger, the supposed heartthrob, is a gnomelike man with a colossal head. It looks as if the units had been borrowed from an novice theater: one scene takes place in an totally unrecognizable Regent’s Park, which, fortunately, is generally hidden by fog, like a Japanese backyard on a fan. In fact, there’s a cemetery, a disfigured mad scientist, some interring and disinterring of corpses, some swordfighting, secret tunnels, moonlit escapes, a profoundly homoerotic scene of a lecherous Miss Colton lotioning Sandra’s scarred again, white shirt pooling on the younger lady’s waist. By that time within the story, Sandra’s leaving the orphanage—somebody has discovered her a job as a governess—however Miss Colton has a secret to inform her first. As soon as the shirt is chastely buttoned, the instructor asks Sandra to hitch her in her room, however Miss Wilkins will get there earlier than Sandra does. Having guessed that the opposite instructor is about to denounce her, Miss Wilkins stabs Miss Colton with a dagger.

Miss Colton dies after revealing that what awaits Sandra is just not a gradual profession as a governess however a nightmarish destiny that has already befallen Victoria Vera. Lower to the opposite woman within the mad scientist’s laboratory, closely sedated and lashed to an working desk, leather-based straps crisscrossing her physique and masks protecting her face because the evil scientist cuts into her skull. With one incision, he turns her right into a residing corpse, a strolling useless woman who, as a substitute of wreaking havoc, is doomed to be loaned out to fulfill the wicked fantasies of males like Lord Ferguson, who appears to be like like he needs to be enjoying a bandit from the Sierra Morena. Now we all know the orphanage’s horrible secret—and Sandra does, too.

From right here on, Sandra, in her white shirt, runs like a soul in torment, narrowly escaping every kind of threats and torments. However on the finish, she finally ends up certain and gagged as regular, again to the silent-movie routine: open eyes, shrieking mouth, physique writhing in simply the fitting method to make her breasts come out of that white shirt. It’s a ridiculous film. Even Camus would say it’s too absurd. We don’t must spend extra time on it, however I simply need you to understand it ends with a merciless anagnorisis: Sandra learns that the person of her desires, the great Dr. Kruger, is actually the depraved, deformed scientist. It is best to actually simply watch Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

In a single interview, Sandra mentioned, “Now that I’m very near having an actual profession, there are folks out to get me. Saying I’m useless, or an exhibitionist, or solely getting solid for my appears to be like. None of that’s true, however I can see why somebody would get that concept from the films I’m in. I’ve simply needed to be a great woman, a educated seal. You understand how the trade is.”

The interviewer asks if she feels that she’s being objectified. Sandra replies, “I wouldn’t say that. I imply, no more than occurs to any lady. And when it occurs, I all the time study one thing from the expertise. You realize, I’ve discovered rather a lot simply being on set. I take courses in my free time—speech, motion, ballet—however my severe training occurs once I get a script. I research my half, see how shut I can get to the character, how utterly I can perceive her. Administrators don’t all the time need you to determine together with your character, however I do. And once I’m rehearsing, I all the time tape myself so I can hear and proper my efficiency. I’d moderately study alone than get a coach, since in the long run, the one individual I’ll all the time have by my facet is myself.”

It breaks my coronary heart to check her rehearsing in her room, wailing, “No, don’t!” and “I’m begging you, please, please let me dwell!” and “Oh!” and “Ah!” and “Ayyy!” into her tape recorder. All that panting, all these muffled shouts and anxious gasps and sobs and unstoppable weeping, and by no means as soon as “O, what a noble thoughts is right here o’erthrown! The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword, th’ expectancy and rose of the honest state, the glass of style and the mould of kind, th’ observ’d of all observers, fairly, fairly down! And I, of women most deject and wretched, that suck’d the honey of his musicked vows” or “Once you durst do it, you then had been a person; and to be greater than what you had been, you’d be a lot extra the person. Nor time nor place did then adhere, and but you’d make each. They’ve made themselves, and that their health now does unmake you. I’ve given suck, and understand how tender ’tis to like the babe that milks me.” No, Sandra Mozarowsky was by no means Ophelia, or Girl Macbeth, or Hedda Gabler.

“One should think about Sisyphus glad,” Camus concludes on the finish of “The Fable of Sisyphus,” having in contrast the absurd man—the person who is aware of, who’s aware of his mortality and of the futility of pursuing transcendence—to the Homeric hero condemned by the gods to eternally roll a boulder up a mountain. Century after century, Sisyphus ascends the mountain, bearing the burden of the rock, which is able to roll to the underside when he’s about to realize his purpose, and down he goes, up, down, up, down—and Camus needs us to think about him glad! He writes, “The battle itself towards the heights is sufficient to fill a person’s coronary heart” (he doesn’t converse of girls’s hearts). “It occurs as nicely that the sensation of the absurd springs from happiness. ‘I conclude that each one is nicely,’ says Oedipus, and that comment is sacred.”

One should think about Sandra glad, glad in the course of the lengthy nights and chilly mornings on set, glad in her coat, or perhaps a cumbersome sweater, ingesting espresso and chatting with the solid and crew whereas she waits for her name, on the brink of shed her coat and kick her footwear off the second she hears “Motion,” to tremble barefoot in her white shirt with its elbow-length sleeves, its neckline that comes as much as her collarbone, although on this scene or the subsequent, by order of the script, it’ll get undone to disclose a shoulder and breast, or else shredded, or spattered with blood, or crumpled on her uncovered stomach whereas some man’s ass strikes rhythmically between her open legs.

I’ve seen Sandra sporting that demure white shirt in El mariscal del infierno, in La noche de las gaviotas, in El colegio de la muerte, in Beatriz, in Pecado mortal, in Practice spécial pour SS, in Ángel negro. I need it to have a which means. Certainly that virginal shirt isn’t only a coincidence. It’s an emblem, a sign, an indication pointing to—what? A bunch of male administrators (she by no means labored with a girl) seeing her in a white shirt, liking the view, and repeating it? Could possibly be. I’m fairly positive I received Camus’s level about absurdity, so I’m not going to give you an entire fable of the shirt. I’m not even going to maintain asking why she performed the identical two roles—the damsel in misery and her reverse, the prostitute—so many occasions. Might a younger actress in Spain aspire to anything on the time?

At seventeen, Sandra complained to the press, “I’m sick of claiming, ‘Sure, this one is destape,’ or ‘No, it isn’t destape.’ Simply flip a coin. Actually enjoying a personality is about much more than whether or not it’s important to take your shirt off. Typically you do, generally you don’t.” However by the point she received carried out capturing in Mexico, she’d modified her tune. She informed ¡Hola! she was “saying goodbye to films” for some time, that she was “sick of all the time enjoying the identical half, sick of script after script the place I’ve to take my shirt off. I’m shifting to London to check English and drama, then coming again to Spain for my baccalaureate, and then I’ll act once more. I like it greater than anything on the planet, however I’m quitting till I’ve the {qualifications} that get you handled as greater than an object.”

One night time, Sandra seems on tv. She’s in her bed room pouting and whining, bursting out of a white gown with heavy, pseudomedieval silver embroidery. The comedian actor Alfredo Landa seems within the doorway, sporting a white tunic over brown breeches and carrying some type of instrument fabricated from a ram’s horn. Involved, he asks, “What’s flawed?”

“Oh, it’s so terrible,” she says, weeping. “I’m so scared. My lock rusted, and I can’t flip the important thing.”

“What lock?”

“On my chastity belt! I put it on and now I can’t get it off,” Sandra says, elevating her skirts to indicate a gilded chastity belt with a large padlock.

This work of cinema known as Cuando el cuerno suena, and it unites me and Sandra in eternity, or in my small, cluttered front room with its heaps of books and drafts and newspapers. I hire my house, so whereas it’s my proper to be right here, I’m nonetheless a precarious resident—of my house and of time, not like Sandra, who’s returned from the useless on my display screen. Camus was flawed to say actors’ glory is ephemeral and fleeting. He wasn’t fascinated with films or tv, the place even one thing as foolish as Cuando el cuerno suena can dwell all the time. You may say it’s not Sandra who’s joined me, simply her look, however Camus says the actor is his look, so right here she is.

Translated from the Spanish by Lily Meyer.

An tailored excerpt from The Shy Murderer, to be printed by Vanderbilt College Press this November.

Clara Usón was a practising lawyer for twenty years earlier than writing her first novel, Las noches de San Juan, which was awarded the 1998 Premio Femenino Lumen. With La hija del Este (The daughter from the east), she grew to become the primary lady to win Spain’s Nationwide Critics Prize. El asesino tímido (The Shy Murderer) was awarded the 2018 Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize, recognizing glorious literary works written in Spanish by feminine authors.

0 Comment