Answering New Questions: Translating Yu Hua’s Metropolis of Fiction, by Todd Foley

Right here type is content material, content material is type.

—Samuel Beckett on Finnegan’s Wake

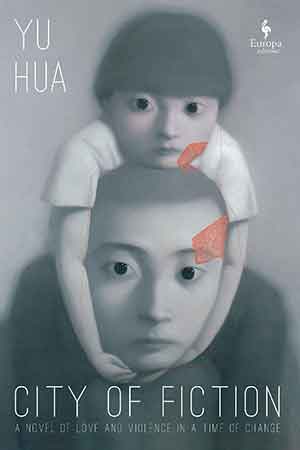

On April 8, 2025, Europa Editions printed Metropolis of Fiction, the English translation of Yu Hua’s advanced novel containing components of epic journey, romance, and household saga, set in opposition to the backdrop of the extraordinary social and cultural improvement of China’s early twentieth-century historical past. On this essay, translator Todd Foley discusses his selections, a few of which resist conforming to extra normal editorial expectations.

The huge distance between English and Chinese language makes the query of translating voice and magnificence particularly fraught. When a Chinese language textual content is dismantled and rebuilt in English, how ought to it sound? What are the foundations for its reconstruction? For all that has been written on the idea of translation, there is no such thing as a clear reply, because the gold normal of “faithfulness” proves to all the time be relative: “trustworthy” to what? Each translation, because it takes form from the idiosyncratic relationship between the unique textual content and the translator’s feeling of it (which is, after all, all the time socially and traditionally contingent), poses these questions anew.

Metropolis of Fiction offered me with some new questions of fashion and voice I didn’t anticipate from Yu Hua. Following his impeccably executed avant-garde modernism of the Nineteen Eighties, Yu Hua’s novels of the previous three many years have all been characterised by brisk, rollicking narratives that critically study current Chinese language historical past up by way of his up to date second. His energetic fashion is often stuffed with fecal matter, blood, guts, and misogynistic sexuality, which all paradoxically coheres round an incisive and tear-jerking social allegory—which itself is merely step one towards the extra severe philosophical tensions his works discover.

Metropolis of Fiction offered me with some new questions of fashion and voice I didn’t anticipate from Yu Hua. Following his impeccably executed avant-garde modernism of the Nineteen Eighties, Yu Hua’s novels of the previous three many years have all been characterised by brisk, rollicking narratives that critically study current Chinese language historical past up by way of his up to date second. His energetic fashion is often stuffed with fecal matter, blood, guts, and misogynistic sexuality, which all paradoxically coheres round an incisive and tear-jerking social allegory—which itself is merely step one towards the extra severe philosophical tensions his works discover.

Metropolis of Fiction, nonetheless, is ready within the early twentieth century, spanning the tip of the Qing dynasty by way of the unruly Warlord Period that quickly adopted the institution of the brand new republic. The historic setting and lack of a direct connection to the up to date second shocked me—how did this novel slot in with the current and with the remainder of Yu Hua’s oeuvre? Furthermore, whereas Metropolis of Fiction strikes vigorously by way of loads of visceral violence and misogyny, it’s characterised by a notably repetitive rhetorical fashion that at occasions conveys seemingly mundane, extraneous particulars. The narrative voice additionally feels fairly simple and plainspoken; though it generally gestures towards classical and early twentieth-century formulations in accordance with the historic setting, general it is extremely accessible and decidedly trendy. Because the translator, I felt the necessity to seize these narrative components—however how and why had been they vital to the novel?

Analyzing the novel’s repetition is one method to get our noses down on the path of this query. Readers will simply discover, for instance, that Xiaomei is all the time decreasing her head, that persons are all the time tucking their arms up into their sleeves, and that “small boats with bamboo awnings” are all around the Wanmudang. Rhetorical repetition, like this instance from chapter 4, can also be frequent:

He felt that Xiaomei possessed a fragile grace he had by no means encountered earlier than . . . even after such lengthy and arduous travels, she remained tender and spirited.

The following day, this tender and spirited girl fell ailing.

Right here we see the chainlike construction of narration this repetition creates, presenting the following info by rhetorically hooking again across the earlier sentence by way of the repetition of “tender and spirited.” The constant repetition all through the novel constructs the story like hyperlinks in a sequence, hooking again round a earlier phrase or picture with a purpose to transfer on to the following.

This chain-link sample and rhythm extends from the smallest stylistic expression in phrases and sentences to the bigger construction of the novel as an entire. The central story of Xiaomei and Lin Xiangfu is considered one of repetitive unions and separations: they start aside, then come collectively of their preliminary assembly; then they separate, reunite, and separate once more. Half 2 of the story then repeats this sample, however from a perspective that focuses on Xiaomei. Mapping their trajectories, one after the opposite as they’re offered within the novel, ends in a sequence:

Importantly, the novel’s ending leaves the standing of the chain’s construction ambiguous: is it a closing reunion or a everlasting separation?

At this level we are able to see the questions raised by this narrative sample lengthen to a deeper degree, projecting into each the previous and future. The undulating sample of the chain essentially implies the fundamental dynamics of course of and alter in conventional Chinese language philosophy, stretching all the best way again to the E book of Adjustments and most famously expressed within the opening line of the basic fourteenth-century novel Three Kingdoms: “The empire, lengthy divided, should unite; lengthy united, should divide.”[i] But it additionally leaves open the query of the novel’s connection to what comes subsequent—how is it linked to the following chaos of China’s twentieth century, with the Second Sino-Japanese Battle and the Cultural Revolution nonetheless to come back? Moreover, how is it linked to the current, and may it inform us something about what lies in retailer?

The undulating sample of the chain essentially implies the fundamental dynamics of course of and alter in conventional Chinese language philosophy.

Whereas this stylistic function of the chain each constructions the novel and hyperlinks it to a broader historic narrative, it could additionally assist us see sure connections with Yu Hua’s different works. The obvious instance is perhaps chapter 26 (half 1), by which Gu Tongnian makes use of his financial benefit to offer free rein to his pubescent wishes. At first look, his extreme indulgence in prostitutes at such a younger age might sound stunning, tasteless, and a bit misplaced. However any reader acquainted with Yu Hua’s main works—as practically all Chinese language readers are—will instantly acknowledge similarities with Baldy Li from his novel Brothers. Baldy Li’s pure, animalistic sexual urges are revealed early on throughout his childhood within the Cultural Revolution, though at that time his solely outlet is self-stimulation and a precarious peek into the ladies’s bogs. Afterward, nonetheless, by channeling his misogynistic wishes by way of the wild neoliberal opportunism of the post-Mao reform period, he turns into insanely wealthy and makes use of his excessive wealth to carry a nationwide magnificence pageant for virgins (which in flip sparks a neighborhood financial system of hymen reconstruction).

This linkage between Metropolis of Fiction’s Gu Tongnian and Brothers’s Baldy Li appears to lift vital questions: What are the underlying options of those moments of fast historic transition that create such comparable characters? What does their comparability say about shifts in worth programs and social constructions, on one hand, and the discharge of capitalist need on the opposite? Whereas Baldy Li totally harnesses the mechanisms of capitalism and ends Brothers by making ready to fly off into outer house, Gu Tongnian is as an alternative tricked into being bought off to Australia, his labor to be exploited by Western capitalists. Why do the paths of those two characters diverge so drastically?

Yu Hua’s fashion of describing characters’ actions might generally appear wordy and repetitive in translation, however this too offers vital hyperlinks to his broader literary considerations. Take this instance from chapter 56, because the residents of Xizhen chase the bandits:

As they ran alongside shouting, they might inform their shouts had been rising fewer and farther between; solely then did they understand there have been just a few of them left.

On this typical formulation, we’re first advised of the characters’ bodily notion of their environment—they hear fewer shouts—and the data is then processed for its human which means (there are just a few villagers left within the chase). Given the prevailing preferences in normal English writing, this line might simply be edited for effectivity and readability, pared right down to one thing like, “The villagers’ shouts decreased as fewer and fewer continued the chase.” However the explicit hyperlink between notion of the bodily world and its human significance has lengthy been a central component of Yu Hua’s writing, maybe most clearly foregrounded in his 1987 story “One Type of Actuality,” by which a baby by accident kills his child cousin by specializing in random exterior stimuli as an alternative of the kid’s security. It’s the mark of a method that Yu Hua made most express in his 1989 essay “Hypocritical Writings”:

I don’t suppose human characters ought to take pleasure in a privileged place in a piece; rivers, daylight, the leaves of bushes, streets, and homes are all equally vital. I believe individuals, rivers, daylight, and the like are all the identical—in an article, all are merely props. Rivers show their need by way of flowing, whereas homes reveal the existence of their need by standing in silence. Human characters, together with rivers, daylight, streets, homes, and all types of props mix to create an built-in complete by way of mutual interplay. . . .[ii]

In Metropolis of Fiction, Yu Hua’s delicate stylistic maneuvers persistently prioritize an goal logic of bodily response that precedes their significance within the human, social realm. What may initially look like verbose prose (or unhealthy translation!) finally ends up linking the novel to an vital and long-standing function of Yu Hua’s fashion of literary illustration.

Extra anomalous in Metropolis of Fiction is Yu Hua’s inclusion of tedious historic particulars, which often interrupt his characteristically fast-paced narrative. Maybe the obvious instance is the outline of assorted varieties of woodworking when Lin Xiangfu goes out to study from the grasp craftsmen in chapter 9. This passage could seem superfluous and repetitive, and within the curiosity of the interpretation’s readability, it might need been considerably condensed or eradicated with out affecting the general plot. Nonetheless, I advocated for its full inclusion due to the vital methods it each hyperlinks the novel to a broader context and factors towards a deeper construction of society. To begin with, the passage attracts a distinction between those that make Western furnishings and conventional artisans—quite than forcing the wooden right into a sure form or type by hammering nails in every single place, conventional woodworkers are so in tune with the wooden and their craft that they not often even want to make use of dowels. Implicit right here is the Daoist philosophy of Zhuangzi, who recounts wheelwright Bian’s description of his work:

If I chip at a wheel too slowly, the chisel slides and doesn’t grip; if too quick, it jams and catches within the wooden. Not too gradual, not too quick; I really feel it within the hand and reply from the guts, the mouth can not put it into phrases, there’s a knack in it someplace which I can not convey to my son and which my son can not study from me. That’s how by way of my seventy years I’ve grown outdated chipping at wheels.[iii]

Woodworking, subsequently, will not be merely a matter of passing down abilities, however as an alternative entails a extra basic understanding by which one’s particular person abilities are couched; it’s from this foundation that the passage then presents us with the intricate and expansive community of occupational specializations. This prolonged dialogue of woodworking thereby offers a specific window by way of which to glimpse the spectacular extent of the financial, cultural, and even ontological material of society that has kind of continued and developed, each consciously and unconsciously, by way of millennia of dynastic rule—solely to now be fully upended by way of the historic forces represented by One-Ax Zhang and the bloody chaos he brings.

Metropolis of Fiction is a narrative of north and south, and Yu Hua’s vigorous but plainspoken and accessible language is the essential hyperlink that joins them.

Lastly, Metropolis of Fiction is a narrative of north and south, and Yu Hua’s vigorous but plainspoken and accessible language is the essential hyperlink that joins them. “Chinese language,” after all, is a quite ambiguous linguistic time period that typically encompasses one frequent system of writing and numerous spoken dialects, all with various levels of mutual intelligibility. Whereas efforts to standardize a contemporary vernacular had been properly underway on the time of the novel’s setting, many of the characters would have had little contact with this, and lots of are illiterate. Yu Hua has famous that the dialogue within the novel was a problem, as a result of he felt “archaic phrases would sound awkward to the reader.” Finally, he says, “I made a decision as long as I didn’t use phrases that sounded distinctly anachronistic, that was adequate.”[iv] Fairly than get slowed down with historic accuracy or the issue of conveying particular native dialects, Yu Hua as an alternative opts for an unpretentious presentation that may usually really feel extra oral than literary. I’ve tried to seize this in my translation by embracing grammatical particles and by generally utilizing barely expanded phrasings when extra environment friendly formulations didn’t strike the fitting down-to-earth tone.

Yu Hua’s accessible narrative voice belies a narrative that in some ways facilities on the difficulties not solely of communication however of the development of narrative itself. Lin Xiangfu intuitively identifies Xizhen as Xiaomei’s hometown due to the dialect, regardless that he can’t perceive it. The town of Wencheng, nonetheless, stays elusive. The title of this imaginary metropolis, which can also be the unique title of the novel, poses some challenges for translation: cheng is an ordinary phrase for metropolis or city, however wen 文 has numerous meanings in Chinese language, together with tradition, civilization, writing, arts, refinement, language, and literature. Our understanding of wen within the title of this fictional, symbolic metropolis might simply contain all of those in a single respect or one other. The interpretation of Wencheng I’ve chosen for the title—Metropolis of Fiction—emphasizes one facet specifically, which is the query of narrative writ giant. Can we ever discover Wencheng, this “metropolis of fiction,” or not? What precisely is that this fiction, and what does it imply for the bigger story Yu Hua is telling of Chinese language modernity?

In China in Ten Phrases, Yu Hua recounts his appreciation of Lu Xun’s “lucid and supple writing”: “When confronting actuality,” he says of Lu Xun, “his narrative strikes with such momentum it’s like a bullet that penetrates the flesh and goes out the opposite aspect, an unstoppable power.”[v] Yu Hua’s narrative voice equally penetrates to the guts of the story, simply as Lu Xun’s groundbreaking use of the vernacular did over 100 years in the past. Very like Lu Xun’s “Diary of a Madman” (1918), by which the madman makes use of the trendy vernacular to precise his notion of the true cannibalistic nature of conventional Confucian society, Yu Hua’s unencumbered language helps reveal the deeper forces which have formed China’s struggles with modernity. In my translation, I’ve subsequently tried to keep away from language that comes with an excessive amount of allusive or intertextual baggage in English. I hope this translation can facilitate equally direct entry for readers in English to Yu Hua’s singularly incisive depiction of Chinese language society.

I hope this translation can facilitate equally direct entry for readers in English to Yu Hua’s singularly incisive depiction of Chinese language society.

In sensible actuality, “world literature” in English, regardless of its purported universality, finally ends up being a style of works that translate properly in accordance with Western literary and aesthetic preferences, that are all the time culturally, traditionally, politically, and ideologically located. What number of works of up to date mainland Chinese language writers, for instance, find yourself on the cabinets of American bookstores—even regardless of Mo Yan’s 2012 Nobel Prize? Given the circumstances, the motivation to adapt a translated Chinese language textual content to sure generic requirements is sort of affordable, as an effort to facilitate the much-needed illustration of Chinese language literature in English. On this translation, nonetheless, as I’ve detailed above, I’ve made a number of selections that resist conforming to extra normal editorial expectations. My efforts to clarify these selections are within the hope that they don’t hinder the studying expertise however as an alternative open up extra methods to understand the excellent and dynamic craftsmanship of this nice author.

* * *

I’d like to precise my deepest gratitude to Yu Hua for permitting me the good honor of translating his work. I wouldn’t have been capable of full this translation with out the steering of Xudong Zhang and the assistance of Wenjin Cui. The great NYU college students in my fall 2021 class “Translation by way of Chinese language Literature” supplied me with considerate and insightful suggestions in our translation workshop, and I’d additionally prefer to thank Annelous Stiggelbout, the Dutch translator of Wencheng, for the useful exchanges we’ve had. Patricia Foley, Larry Foley, and Lou Johns gave me probably the most essential reward of time to truly full the interpretation. Anne Mulhall, Peter Jones, and Sharon Ostfeld-Johns are my guiding lights of artistic expression, and I’d prefer to dedicate my efforts on this translation to Sharon and our youngsters, Cliff and Pepper.

New York University

0 Comment