A Man Is Like a Tree: On Nicole Wittenberg

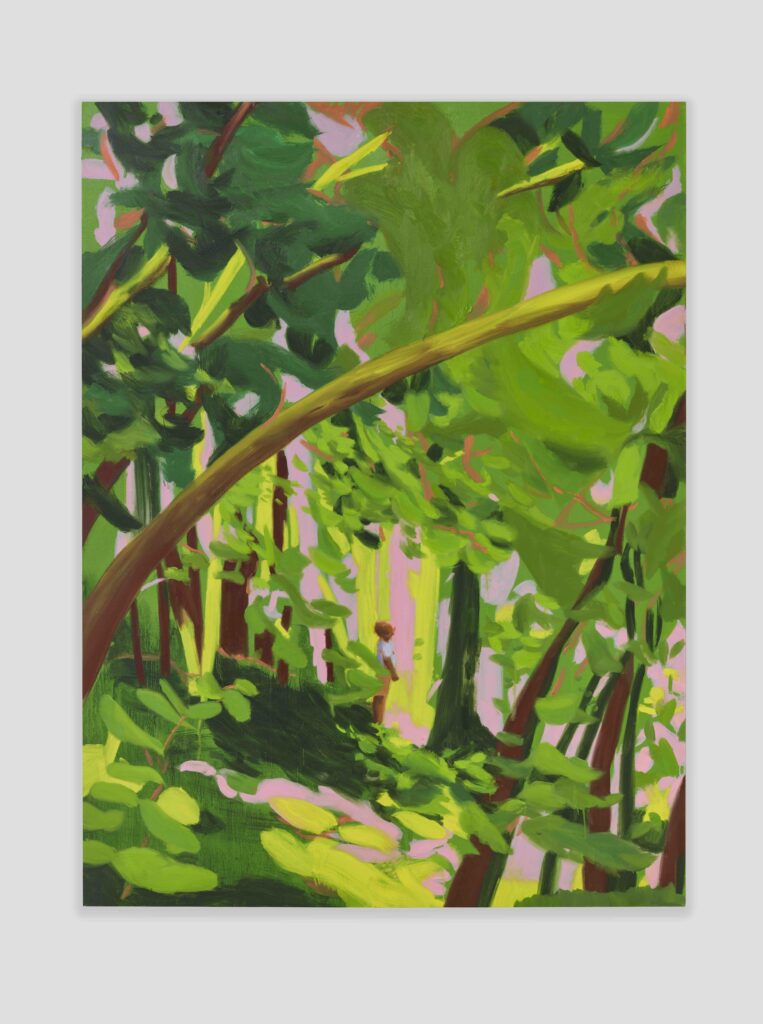

Nicole Wittenberg, Woods Walker 7 (2023–2024), oil on canvas, 96 x 72″.

Nicole Wittenberg has painted quite a lot of topics during the last fifteen years, however two predominate: lush and lyrical landscapes, usually of locations the place water meets land—typically unpopulated, however with an occasional determine glimpsed among the many timber, as if to supply focus and scale—and her much less well-known male nudes (together with an occasional pulchritudinous feminine counterpart), usually engaged in intercourse acts which have seldom been depicted in Western excessive artwork. These photos present sexual beings up shut and private, although possibly up shut and impersonal is extra to the purpose. They’re workouts in concision and viewpoint; in case you get shut sufficient, something seems to be massive, and these dicks look monumental, like massive timber in a low-rise panorama.

Regardless of their provocative, even polemical material (why not paint dicks?) Wittenberg’s work of blowjobs and the type of self-care generally often known as jerking off are additionally involved with type, with the how of portray as inseparable from the what. In work like Blow Job and Purple Handed, Once more, each from 2014, the how depends on a gesture that’s high-risk and directionally sound. It’s the exact placement together with a sure velocity that enables the gesture to stick to the shape. By way of accuracy of brush mark, Wittenberg could be the Franz Kline of dick work. You need to paint one thing, and you might as properly paint what pursuits you. Generally you may paint what pursuits others, to see if it additionally pursuits you. Are these work pornographic? I don’t know, possibly. I don’t actually care—maybe that descriptor is even a praise. I’m not particularly polemical in my method to artwork or to life, however suffice it to say that the analytically sexual gaze in portray ought to be equally and unreservedly obtainable to all. These are work that say, Oh, is that this picture making you uncomfortable? Recover from it.

Nicole Wittenberg, Purple Handed, Once more, 2014, oil on canvas, 36 x 48″.

Wittenberg’s panorama work and pastels, alternatively, belong to an extended ancestral line; they derive, meanderingly, from among the earliest work produced on this nation, they usually represent a recent reframing of a potent and intently held self-image: the sense of marvel engendered by the pristine vastness of the North American panorama. It’s as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in regards to the early Dutch settlers crusing into New Amsterdam, seeing for the primary time the “recent, inexperienced breast of the brand new world.”

Wittenberg posits two fundamental visions of this Arcadian heritage, the peopled and the unpeopled panorama, and each stem from her time residing among the many shallows and the depths of coastal Maine, the place she has summered the final dozen or so years. One kind of image reveals a densely wooded grove bordered by water, seen from the center distance within the vague mild of early morning or night. In these seminocturnes, the panorama is shadowy and mysterious, kind of inaccessible—maybe the view from a ship of one of many innumerable uninhabited islands that dot the Penobscot Bay, as in Cradle Cove (2022). Or the view from the shore as we ponder a stand of timber midway to the horizon within the fading pink mild, as in After the Storm (2024). The illumination is dim; the timber are backlit and the colours of the woods and water in addition to sky are all darkish and close-valued. These photos are portents of existential unease, of loneliness and one thing unresolved, and as such are a continuation of a soulful lineage; one feels Marsden Hartley standing behind them, and behind Hartley stands Albert Pinkham Ryder. Wittenberg’s luminous, unpeopled landscapes have a intently held, inside feeling of one thing that resists us, of an consciousness simply out of attain.

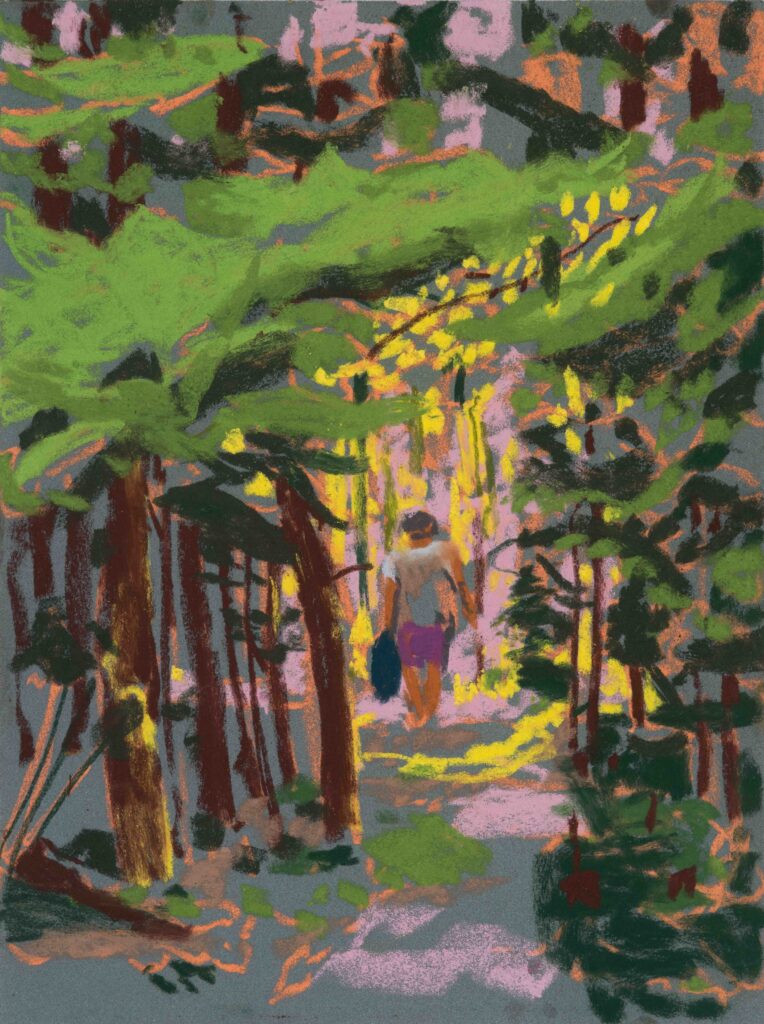

Nicole Wittenberg. Woods Walker (2021), pastel on paper, 15.5 x 11.5″.

The opposite kind of panorama portray can also be of the Maine woods however seen from inside a grove of towering white pines. It’s maybe noon, the distinction between mild and shadow is excessive, and a solitary determine wends his means beneath the swooping branches. These are the Woods Walker work, of which Wittenberg has painted quite a lot of variations. The addition of the only determine marked a turning level in her artwork; we’re contained in the forest now, the determine is our surrogate, and although extra of a participant within the passage of minutes and hours and the change in mild, we’re nonetheless weak to the vicissitudes of nature, climate, and reminiscence. The unstated fear: Will we have the ability to discover our means again? The ebullience one feels in that second, strolling within the sensible mild, arms swinging by one’s sides, could also be short-lived.

Wittenberg’s work all share a priority for compression and for scale: dicks as massive as timber and timber towering over diminutive hikers. Each are a perform of viewpoint, which itself constitutes the painter’s first decisive act. The viewpoint goes a good distance in setting an image’s narrative functionality. We solely see what the painter chooses to point out us; what’s unnoticed will not be our concern. We will’t know what occurs within the subsequent on the spot, or after we cease trying. The thriller continues to unfold, with us or with out us. This actual high quality of sunshine—maintain it! Within the subsequent on the spot it modifications, without end. The melancholy of portray.

David Salle’s essay “A Man Is Like a Tree” will seem in Nicole Wittenberg, the primary survey of Wittenberg’s work, which might be revealed by Phaidon in July. The publication of the ebook coincides with two solo exhibitions of the artist’s work, on the Ogunquit Museum of American Artwork and the Heart for Maine Up to date Artwork.

0 Comment