Tracings

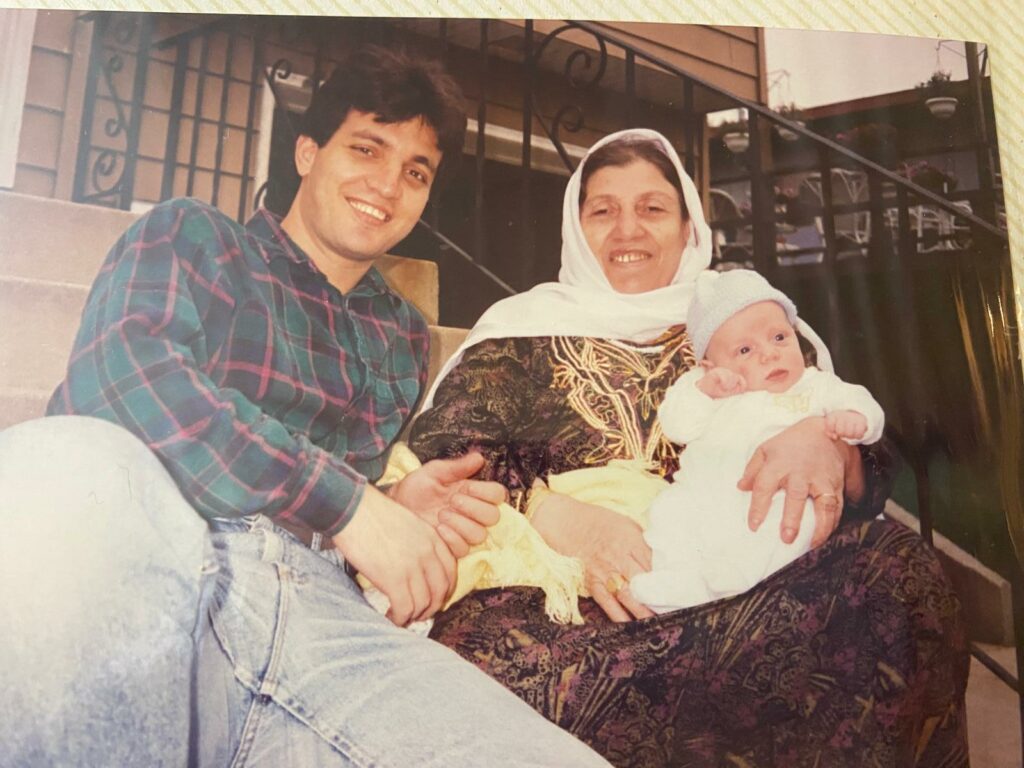

At middle, the creator together with her father and her grandmother. {Photograph} courtesy of Sarah Aziza.

Often, after we have been small, our father spoke to us of geography.

Daddy is from a spot known as Palestine, he mentioned, in a lesson captured by my mom on the household’s camcorder. Within the footage, my father sits in a small rocking chair, brown eyes intent, somewhat shy. My youthful brother and sister are absorbed by the array of blocks on the ground, however I’m near my father’s ft, my fluffy blond head thrown again, mouth pink and agape. He holds up a globe, his fingers sliding towards a sliver of brown and inexperienced. He tilts it towards me to disclose cramped lettering: Israel/Palestine.

I hop as much as look, my nostril practically skimming the painted plastic as I squint on the hair-thin ink. I’m vaguely conscious of a factor known as nations, loosely greedy that these are locations full of individuals which are like—however not like—me. There is no such thing as a point out, right this moment or any day that I can recall as much as that time, of the primary half of that forward-slashed title, that factor known as Israel. There aren’t any tales of shed blood, no wistful tributes to a misplaced homeland. My father merely hops his fingers, leaping a long time and tragedies. Due south, he factors to an orange rectangular slab of land. That’s Saudi Arabia. That’s the place Sittoo lives. My father makes use of the فلاحي phrase sittoo—honored woman—our dialect’s time period for grandmother. I squint once more, attempting to see her.

My grandmother, like these nations, feels essential and imprecise. It might be one 12 months earlier than she got here to stay with us and two years earlier than we uprooted and moved to Jeddah, her adopted metropolis by the ocean. In our lesson, my father didn’t linger, didn’t attempt to bridge the distinction between Jeddah and Palestine. As a substitute, the video exhibits him smiling, rolling the world to my left. He lands on a inexperienced sprawl labeled the USA. His finger faucets one other dot, Chicago, which clings to a lake formed like a tear.

And right here is the place we stay, my father concludes, his voice a flourish. Impressed by the blue distance between there and right here, I blurt, Woooooah. These are … these are two faraway locations! My father seems to be up on the digicam, his face twitching with repressed laughter. That’s proper, habibti, he replies, attempting to match my seriousness. The lesson ends right here. I’ve loved the eye of my father, taking part in with this ball known as the World. However afterward, I stay simply as bewildered by two images hanging down the corridor.

On the far finish of a row of household portraits, these two have been smaller than the remaining. Day by day, I handed by them, attempting in useless to avert my eyes. Every time, I failed, again of my neck pricking as I raised my head to stare. The primary photograph is small, its body an affordable imitation gold. Inside floats a black-and-white picture of a barefoot little boy. He squints in long-gone sunshine, a crease within the photograph chopping a furry line above his forehead. He bears a placing resemblance to my brother, but his cautious eyes defy intimacy.

I requested my mom, uneasily, about this stranger. She knowledgeable me that this boy was my father, standing in a spot known as Gaza. A reputation with serrated edges, a phrase I’d not hear once more till years later, buzzing on TVs. Her clarification ended there, and I felt with unusual certainty that I used to be not meant to ask extra. As a substitute, I studied the pictures—the sand and particles on the boy’s ft. Jagged shadows, bleaching mild. The entire scene left me feeling each lonely and alarmed.

The second photograph was higher preserved, and extra ominous to me. A black-and-white portrait of the identical small boy together with his mom, posed unsmiling facet by facet. The lady solely vaguely resembled the grandmother I’d come to know. Nonetheless in her thirties, her cheekbones have been full and clean, her thick black hair tied in a free ponytail. She unnerved me together with her dead-forward stare, the grim line of her mouth. The boy tilted towards her, concerning the digicam skeptically, as if able to defend.

These images jarred with the others on the wall. The remaining have been poised, inviting, blooming from sepia to paint. Pictures of my mom’s childhood: a blond woman in bobby socks. An image of her personal mom, a girl with coiffed hair, fingers resting on a harp. Shiny images of our younger household, taken in a Kmart studio towards a blue-cloud wall. My creativeness roamed simply inside these frames. However I handed my eyes over the nook that held my father and his mom. them instantly left me chilly, swimming in one thing I couldn’t title.

***

My grandmother, a younger girl in sixties Gaza, woke usually with a thudding chest, the evening tangled in her hair. With my younger father in tow, she sought solace from neighborhood ladies. One learn that means in espresso dregs, peering into small porcelain oracles. One other, Sheikha Amna, provided prayers and protecting charms to safe the youthful girl’s destiny. These ladies granted my grandmother story within the chaos of exile, purpose and company inside loss. However later she ceased looking for such solace. قدر الله—in issues of destiny, it was finest to contend quietly. The blue plumes of her bakhoor wafting wordless, heavenward.

Within the realm of data, her hint has at all times been slight. Born with out a start certificates within the days of British rule, her title was first written in 1955. A UN employee made the inscription—as soon as in English, as soon as in French—and handed her the paper slip. Her title, a token traded for sugar and wheat, in languages she couldn’t learn. She would have been roughly thirty then, a refugee of seven years, mom to a daughter and three sons.

Earlier than, in her Palestinian village of 600, names have been recognized by coronary heart. She was bint Mohammed al-Mukhtar, ibn Yousef. Her lineage, a sequence of masculine names, a tether to time and place. Her city, ʿIbdis, first appeared in Ottoman information in 1596, and will date to the Byzantine interval between the third and sixth centuries, as Abu Juwayʾid.

The Ottoman officers in ʿIbdis marked down thirty-five households that 12 months, not bothering with names. Their curiosity was in dunum, the wealthy fields yielding wheat, barley, and honeybees. Later, the villagers added grapes and oranges alongside olives, chickens, and mish-mish. A whole lot of cities like ʿIbdis dotted the rolling countryside. Every had its defining characteristic, preserved in tales and poetry. ʿIbdis’s boast was its jamayza, the stately sycamore tree.

Horea was the title given to her when she was born. حورية, straightforward to mistake for حرية—freedom. Typically, I want حرية was her title. The that means of حورية just isn’t fastened however hovers round lovely girl. Typically translated as nymph, a phrase discovered centuries again in poetry and Qurʾanic verse. In English, it may also be rendered as dark-eyed magnificence. Typically, virgin of paradise. Some hadith, with a touch of colorism, describe a girl so beautiful her flesh glows translucently. Is that this what makes an angel? One thing desired and vanishing?

But her girlhood was a sturdy-bodied factor. She was daughter of the mukhtar—chosen one, a mayor of types, a person appointed to steer village affairs. For her, mom was a number of. Horea was raised by her father’s a number of wives; then, after her father’s demise and mom’s remarriage to a person on the Gazan coast, she was tended by a sister-in-law. There, Horea’s world was woven of half siblings, cousins, and the company her brother Fawzi entertained.

Like most different village ladies, she was by no means despatched to highschool. As a substitute of holding pencils, her fingers grew deft at taboon dough, spark-quick as she flipped white-bellied bread over flame. As a younger spouse, she carried lunch every day to her husband within the subject. Passing neighbors on the best way, they embroidered greetings within the air. She set down the basket of bread at her husband Musa’s ft. Might Allah offer you power. Receiving, he mentioned, Might God bless your fingers. After consuming, she yoked her afternoon to his. Collectively, they labored the land till night known as them in.

***

These have been the times she later saved tucked inside her, hidden from my father and from me. Horea embalmed her childhood in silence, ʿIbdis shrouded in imprecise fable. My father wouldn’t glimpse this historical past till a long time later, as Horea led him via its ruins, the previous spelled in scattered stone. His timeline started in Deir al-Balah, a metropolis in Gaza famous for not sycamore however its date palms. He was born there in 1960, his start registered by the Egyptians who, in 1948, changed British occupiers after halting Israel’s southern advance. On his start certificates, ʿIbdis hovers within the white house across the phrases GAZA STRIP.

Horea welcomed her fourth and final born, Ziyad, in a UN clinic alone. Her husband was 4 years deep in ghourba, a post-Nakba financial exile cobbling a meager dwelling within the Gulf. She carried her new child residence on foot, her steps jaunty, jubilant. With Ziyad, there would now be 4 of them sharing the 2 rooms Horea had constructed on an unused lot of land. This, a everlasting makeshift shelter after months of ready for NGO housing. The one furnishings stood within the sand outdoors—an previous desk her second-born, Ibrahim, used as a desk. He was the household’s brightest, with goals of medical faculty. To its left, an space for kneading dough and a banana tree that refused fruit.

Like several youngster, my father was born to belief. Gaza was Falasteen was residence was the world. Ziyad beloved the small path his days carved, barefoot, between his mom’s lap and the seaside. Mornings, he woke to the coo of pigeons, a flock Horea raised and cooked on Friday after prayers. At these meals, he jostled his brothers for a double portion of meat. Above him, historical past webbed, conjured within the phrases of Horea and her company. On occasion, he heard a moan slip from one and caught a chill. He glanced as much as see his mom’s head shake, her shoulders slack. However these have been solely passing, distant clouds. ʿIbdis, conflict, and even your father—seldom spoken instantly, these phrases had no our bodies, no weight. With earlier than locked away, he didn’t see his life as aftermath.

There are sorts of affection that cease language in its tracks. Maybe she held again ʿIbdis’s title to reserve it from the previous tense. An absence spoken gathers mass, asking the physique to bear it twice. Perhaps her silence was a refusal, a declaration that grief shouldn’t be her sons’ inheritance. In the long run, survival is a language, a logic all its personal.

But ʿIbdis wanted no talking; it echoed in every thing. It flickered within the eyes of her cousins as they circled misplaced acres of their heads. It lived within the sturdy music of their dialect, consonants like hilltops, reminiscence tucked inside تعبيرات. It hovered within the style of bread, baked from UN-issued flour. The flat sameness of its texture recalled how the dough in ʿIbdis rippled, grainy with hand-milled gamah. Every chew a morsel of the months previous—rain or dryness, farmers’ fear, fingers plucking, then grinding kernels of gold.

This essay is customized from The Hole Half, which will probably be printed by Catapult in April.

Sarah Aziza is a Palestinian American author and translator. Her journalism, poetry, and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, The Baffler, Harper’s, Mizna, the Intercept, the Guardian, and the Nation.

0 Comment