How Big Robotic Captured Asian America

The primary subject of the journal Big Robotic I ever got here throughout featured the Hong Kong actor Tony Leung Chiu-wai on the quilt—this was sufficient to face out on a crowded newsstand within the mid-nineteen-nineties. However what caught my consideration had been the teasers for a random assortment of different tales, about gangs, browsing, shaved ice, orgies. A small tagline within the prime proper nook learn “{A magazine} for you.” However who was I? I used to be a teen-ager and determined to know. I suspected Big Robotic might assist me determine it out.

For anybody underneath the age of forty, this degree of impressionability may sound a bit foolish. However this was a time when there have been few issues as intoxicating as a bountiful journal rack, with numerous pursuits, ideologies, identities to strive on for dimension. Lately types and reference factors float freely; again then the concept one might bridge silos, admitting an affection for, say, each punk rock and Whats up Kitty, felt jarring. There was one thing about Big Robotic’s affection for Asian tradition—and its allergy to dwelling on what that meant—that drew in lots of younger individuals, like me, who had been trying to find a context. It was {a magazine} that was very severe about some issues, and in no way severe about others.

Eric Nakamura began Big Robotic in 1994, having not too long ago left his job at Larry Flynt Publications, a Los Angeles media empire that printed magazines starting from VideoGames (the place Nakamura had discovered work proper out of school, as an editor) to Rap Pages and Hustler. His experiences at Flynt prompt that making {a magazine} wasn’t too onerous. He put collectively a sixty-four-page zine, stapled and xeroxed, concerning the issues that fascinated him and his pals: sumo wrestling, the Japanese noise band Boredoms, kung-fu motion pictures, courting. He invited Martin Wong, a kindred spirit he’d seen round at punk reveals, to jot down and to assist distribute the 2 hundred and forty copies of the zine’s preliminary run.

“We had been simply writing about stuff we favored,” Wong, who was working as an editor at a textbook firm on the time, stated. “We weren’t making an attempt to outline something or change something.” For the second subject, Wong wrote about his expertise dressing up as Whats up Kitty for a Sanrio pageant in Southern California, and the surprisingly vitriolic issues passersby stated to him (“I hate you,” “Get a life”). Wong quickly turned Big Robotic’s co-editor, and by the fourth subject that they had graduated from D.I.Y. folding and stapling to a standard-size, nationally distributed journal with a full-color cowl, albeit one which was nonetheless sustained by volunteer labor. In 1996, Big Robotic turned a quarterly, and by the late nineteen-nineties they had been publishing as much as six instances a yr, with a circulation that peaked within the early two-thousands at round twenty-seven thousand. What attracted individuals from the mid-nineties by 2011, when Big Robotic printed its ultimate subject, was its combination of vanity—the sense that it was made by individuals with a strident sense of style—but in addition curiosity. This run is the topic of “Big Robotic: Thirty Years of Defining Asian American Pop Tradition,” a lavishly designed hardcover ebook, simply printed by Drawn & Quarterly, that collects a number of the journal’s most essential articles, in addition to recollections from contributors and readers.

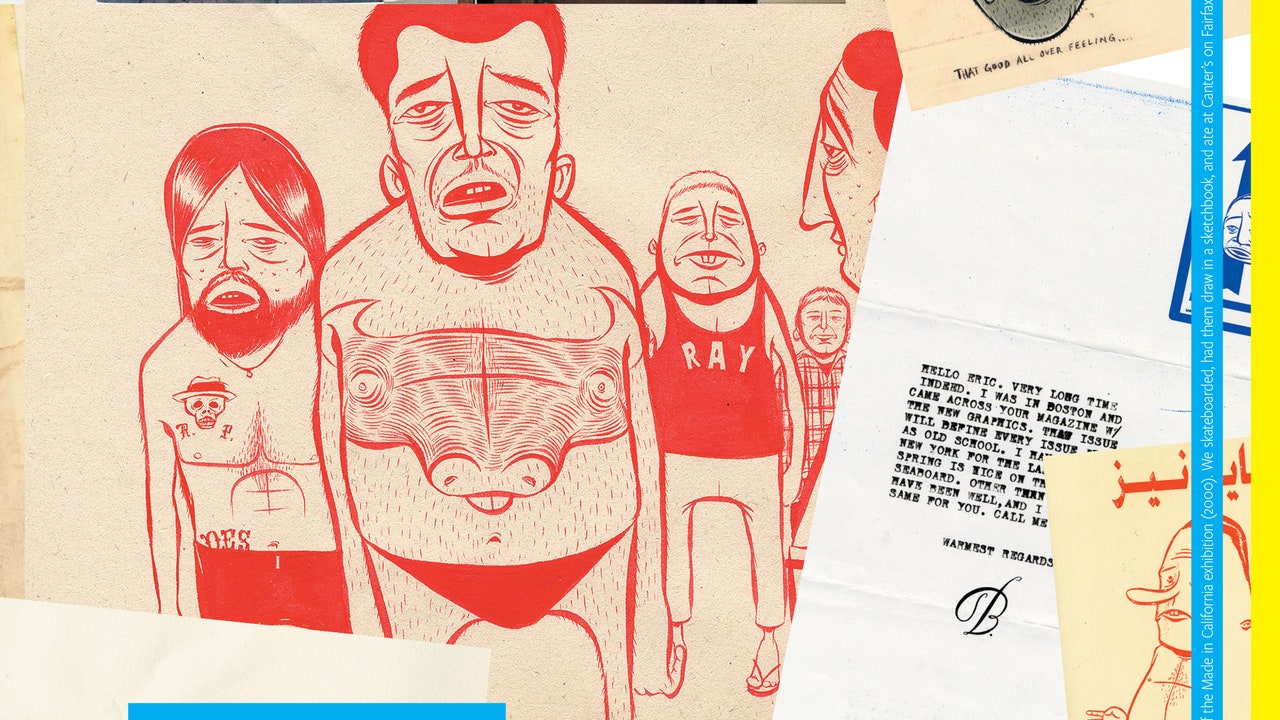

{Photograph} by Eric Nakamura / Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly

“Big Robotic”—edited by Nakamura, together with Francine Yulo, Tracy Hurren, Megan Tan, and Tom Devlin—reprints a consultant cross-section of items, arranging them thematically moderately than chronologically. Claudine Ko, one in every of Big Robotic’s most vigorous contributors within the late nineties and early two-thousands and now an editor for the Occasions’ T Model Studio, presents a remarkably complete introduction to the journal, particularly its early days. In Ko’s telling, there was no grand imaginative and prescient, only a fixed have to fill pages. In 1996, Wong proposed a bit about Manzanar, the positioning of one of many focus camps the place individuals of Japanese descent had been imprisoned throughout the Second World Struggle, which his household usually drove previous on their ski journeys to the close by Sierra Nevada mountains. Wong and Nakamura—whose father had been incarcerated on the Poston camp, in Arizona—packed their skateboards and determined to take a street journey.

The outcome was “Return to Manzanar,” a solemn but rebellious piece of writing. Wong notes the names etched into the reservoir partitions by “vandal Manzanar internees” and talks with Sue Embrey, who was imprisoned there as a teen-ager, about whether or not she believes the positioning is haunted. His piece tries to revive some nuance to the lives of those that had been trapped there. It was, he writes, a spot the place individuals “gardened, painted footage, printed newspapers, composed poetry, made infants, and performed volleyball and baseball,” making essentially the most out of a horrific scenario. Wong and Nakamura skate by the park, doing methods off a monument, questioning what the individuals driving by thought “on the sight of skate boarders in the course of hell.” As Nakamura explains to Ko within the ebook, “It’s taking possession of an in any other case fucked-up place.”

A meandering interview model was attribute of nineties zines, instructing you as a lot concerning the interviewers and their whims as whomever they had been speaking to. There’s a very candid and wide-ranging dialog between Nakamura and Tony Leung Chiu-wai. The actor appears to overlook that he’s baring his soul about his lowest moments to what was then simply an obscure American zine. “At one time, I wished to commit suicide as a result of I couldn’t get myself out of my character,” he says, recounting an early second in his profession. “You must fake you’re others at work, then you definitely get so confused inside you.” Because the dialog continues, you’ll be able to nearly sense Nakamura’s astonishment that Leung remains to be on the road, because the actor solutions more and more random questions on how he perfected his hair model and whether or not he’d ever had a nostril ring. When Nakamura and Wong interview the actress Maggie Cheung, they one way or the other find yourself speaking about her teen years, when she recognized with the British mod subculture. They ask her point-blank, “Are you bizarre?” “I don’t know,” she replies. “I’m simply me.” In Ko’s interview with the filmmaker Wong Kar Wai, she remarks that Wong makes Asian individuals “look cool” in contrast with their portrayal in American movies. He merely says, “Asian individuals are cool.”

Studying Big Robotic, you bought the sense that something was value reviewing—snacks, books, motion pictures, seven-inch singles, Asian canned espresso drinks—and everybody was value interviewing, if solely in order that you might be taught slightly extra concerning the world round you. One of many odder interviews the journal printed resulted from a letter Nakamura acquired from an unlikely reader: Wayne Lo, a mass shooter who, in 1992, killed two individuals and injured 4 others at Bard Faculty at Simon’s Rock, the place he was a scholar. The 2 exchanged letters, and Nakamura finally visited him in jail. His questions on Lo’s recollections of the capturing, and the day-to-day routine in jail, are curious and blunt. (“What’s the jail like?” “Are you pals with any guards?”) Lo appears placid and bemused—till the top, when Nakamura asks him concerning the T-shirt that he famously wore on the night time of the crime, which marketed the New York hardcore band Sick of It All. Lo admits that he merely dabbled in punk, and that the shirt was only a coincidence. “I like glam metallic,” he tells Nakamura. “Music died when grunge emerged.”

0 Comment